Containers are ephemeral by design and running stateful applications on Kubernetes requires different architectural patterns, specifically for persistent storage. Databases, content management systems and enterprise applications need persistent storage that survives pod restarts and node failures. This is where Kubernetes block storage solutions become critical infrastructure components.

Cloud providers offer managed storage options while traditional SANs provide enterprise-grade reliability. However, many teams need a simpler, portable solution that works consistently across any infrastructure from bare metal and edge deployments to multi-cloud environments. Enter Longhorn storage.

Longhorn is a lightweight, distributed block storage system for Kubernetes and a CNCF Incubating project originally developed by Rancher Labs and later donated to the CNCF. Longhorn storage provides enterprise-grade persistent storage without the complexity or cost of traditional storage arrays. It transforms local disks on your Kubernetes nodes into a replicated, distributed storage system using containers and microservices that are fully orchestrated by Kubernetes itself.

In this comprehensive guide to Kubernetes block storage, we will talk about Longhorn’s architecture, explore its data protection mechanisms, and provide the technical details you need to evaluate Longhorn for your stateful Kubernetes workloads.

Longhorn Architecture – Under The Hood

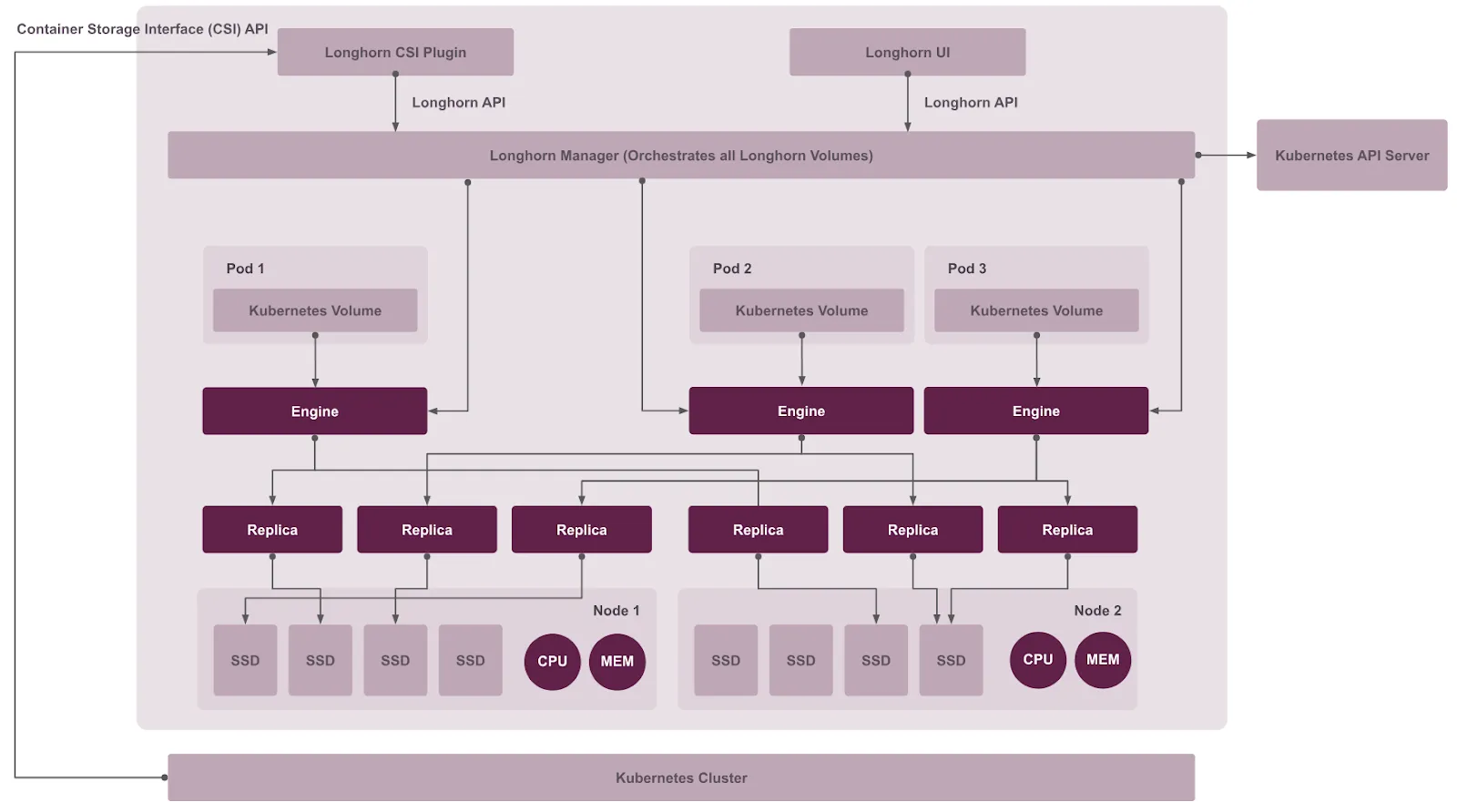

Longhorn implements a microservices-based architecture where storage operations are distributed across multiple components. Unlike monolithic storage controllers that manage thousands of volumes, Longhorn creates a dedicated controller for each block device volume. This design isolates failure domains: a controller crash affects only a single volume, not your entire storage infrastructure.

Core Components

The Longhorn system consists of four primary components working together:

Longhorn Manager which runs as a DaemonSet on every node, and acts as the control plane. It handles API requests from the Longhorn UI and CSI plugin, orchestrates volume creation and replica placement, and maintains desired state across the cluster.

Longhorn Engine that serves as the data plane component responsible for all I/O operations. Each volume gets its own dedicated Engine instance that always runs on the same node as the pod using the volume. This co-location reduces latency by keeping I/O traffic local and also coordinates synchronous writes across all replicas.

Longhorn replicas which stores the actual volume data as multiple copies for redundancy. Each replica runs as a separate process, distributed across different nodes to ensure high availability. The default configuration maintains 3 replicas per volume, allowing the volume to tolerate N-2.

CSI Driver provides Kubernetes integration through two components: the CSI Controller handles volume provisioning, deletion, and snapshots, while the CSI Node Plugin runs on every node to mount volumes and manage iSCSI connections. Together, they convert Kubernetes PVC requests into Longhorn volume operations following the CSI standard.

Architecture diagram of Longhorn components. Source: Longhorn documentation.

Data Storage and Disk Management

Understanding how Longhorn stores data is crucial for capacity planning and performance optimization. Longhorn’s hyperconverged approach uses local node storage efficiently through sparse files and flexible disk configuration.

Longhorn follows a hyperconverged architecture where storage and compute run on the same physical nodes. By default, data is stored at /var/lib/longhorn on each node, with replicas organized in /var/lib/longhorn/replicas/<volume-name>/ as directories.

Each replica contains volume data as sparse files – which only consume disk space for actual written data and not the full allocated capacity. This ensures that a 100GB volume with 10GB of actual data uses only ~10GB on disk. It also supports multiple disks per node beyond the default path. Additional disks can be added with disk tags like ssd or fast.

Data Engine Options

The data engine is the core component that handles all I/O operations between applications and storage. Longhorn offers two engine implementations each with different performance characteristics and use case suitability.

V1 Data Engine is the default, stable implementation using traditional iSCSI-based block storage. It’s production-ready, supports all Longhorn features, and is suitable for general-purpose workloads, CI/CD pipelines, and edge computing.

V2 Data Engine is an experimental feature based on SPDK (Storage Performance Development Kit) that offers 2-4x improvement in write IOPS and 50-70% lower latency compared to V1. However, it requires kernel 6.7+, consumes a full CPU core per node due to SPDK polling mode, and is not recommended for production environments. Read more about V2 Data Engine.

Volume Access Modes

By default, Longhorn volumes support ReadWriteOnce (RWO) mode where only one pod can write at a time. However, some workloads like shared caches or content management systems require ReadWriteMany (RWX) mode, where multiple pods across different nodes need simultaneous write access to the same volume.

It supports RWX access mode through an NFS-based implementation. For each active RWX volume, Longhorn creates a dedicated share-manager-<volume-name> pod that runs an NFSv4 server, exporting the underlying volume. A corresponding Kubernetes Service provides the NFS endpoint, allowing multiple pods to mount the volume simultaneously.

This approach requires NFSv4 client installation on all nodes and makes the Share Manager pod a single point of access. All I/O is funneled through this one NFS server pod, which can become a bottleneck for write-heavy workloads. Read more about volume access modes in Longhorn.

Data Replication Model

High availability requires data to exist on multiple nodes. Longhorn achieves this through synchronous replication – ensuring every write is confirmed on all replicas before acknowledging success to the application.

The Longhorn engine exposes each volume as an iSCSI target, with Kubernetes nodes acting as iSCSI initiators. When an application writes data, the request flows through iSCSI to the Engine, which simultaneously writes to all healthy replicas in parallel. The write is acknowledged only when all replicas confirm success – ensuring strong consistency across the distributed system.

If a replica fails, the Engine continues operating with the remaining replicas while automatically rebuilding the failed one on a healthy node. Read more about replicas in Longhorn.

Installation and StorageClass Configuration

Longhorn can be deployed on any Kubernetes cluster using Helm or kubectl.

Pre-requisites

- Kubernetes v1.21 or later

- open-iscsi installed and iscsid daemon running (required for iSCSI block device connectivity)

- nfs-common or nfs-utils package installed (required for RWX volumes)

You can verify your environment using the Longhorn Command Line Tool which checks the prerequisites and configurations.

# Download longhornctl (AMD64)

curl -sSfL -o longhornctl https://github.com/longhorn/cli/releases/download/v1.10.1/longhornctl-linux-amd64

# Make it executable

chmod +x longhornctl

# Check prerequisites

longhornctl check preflight

INFO[2025-08-22T12:58:40+08:00] Initializing preflight checker

INFO[2025-08-22T12:58:40+08:00] Cleaning up preflight checker

INFO[2025-08-22T12:58:42+08:00] Running preflight checker

INFO[2025-08-22T12:58:49+08:00] Retrieved preflight checker result:

ip-10-0-1-132:

info:

- Service iscsid is running

- NFS4 is supported

- Package nfs-client is installed

- Package open-iscsi is installed

- Package cryptsetup is installed

- Package device-mapper is installed

- Module dm_crypt is loaded

warn:

- Kube DNS "coredns" is set with fewer than 2 replicas; consider increasing replica count for high availability

INFO[2025-08-22T12:58:49+08:00] Cleaning up preflight checker

INFO[2025-08-22T12:58:50+08:00] Completed preflight checkerInstallation using Helm

# Add the Longhorn Helm repository

helm repo add longhorn https://charts.longhorn.io

# Update to fetch the latest charts

helm repo update

# Install Longhorn in the longhorn-system namespace

helm install longhorn longhorn/longhorn \

--namespace longhorn-system \

--create-namespace \

--version 1.10.1

# Verify Installation

kubectl -n longhorn-system get pod

NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE

longhorn-ui-b7c844b49-w25g5 1/1 Running 0 2m41s

longhorn-manager-pzgsp 1/1 Running 0 2m41s

longhorn-driver-deployer-6bd59c9f76-lqczw 1/1 Running 0 2m41s

longhorn-csi-plugin-mbwqz 2/2 Running 0 100s

csi-snapshotter-588457fcdf-22bqp 1/1 Running 0 100s

csi-snapshotter-588457fcdf-2wd6g 1/1 Running 0 100s

csi-provisioner-869bdc4b79-mzrwf 1/1 Running 0 101s

csi-provisioner-869bdc4b79-klgfm 1/1 Running 0 101s

csi-resizer-6d8cf5f99f-fd2ck 1/1 Running 0 101s

csi-provisioner-869bdc4b79-j46rx 1/1 Running 0 101s

csi-snapshotter-588457fcdf-bvjdt 1/1 Running 0 100s

csi-resizer-6d8cf5f99f-68cw7 1/1 Running 0 101s

csi-attacher-7bf4b7f996-df8v6 1/1 Running 0 101s

csi-attacher-7bf4b7f996-g9cwc 1/1 Running 0 101s

csi-attacher-7bf4b7f996-8l9sw 1/1 Running 0 101s

csi-resizer-6d8cf5f99f-smdjw 1/1 Running 0 101s

instance-manager-b34d5db1fe1e2d52bcfb308be3166cfc 1/1 Running 0 114s

engine-image-ei-df38d2e5-cv6nc 1/1 Running 0 114sAccessing the UI

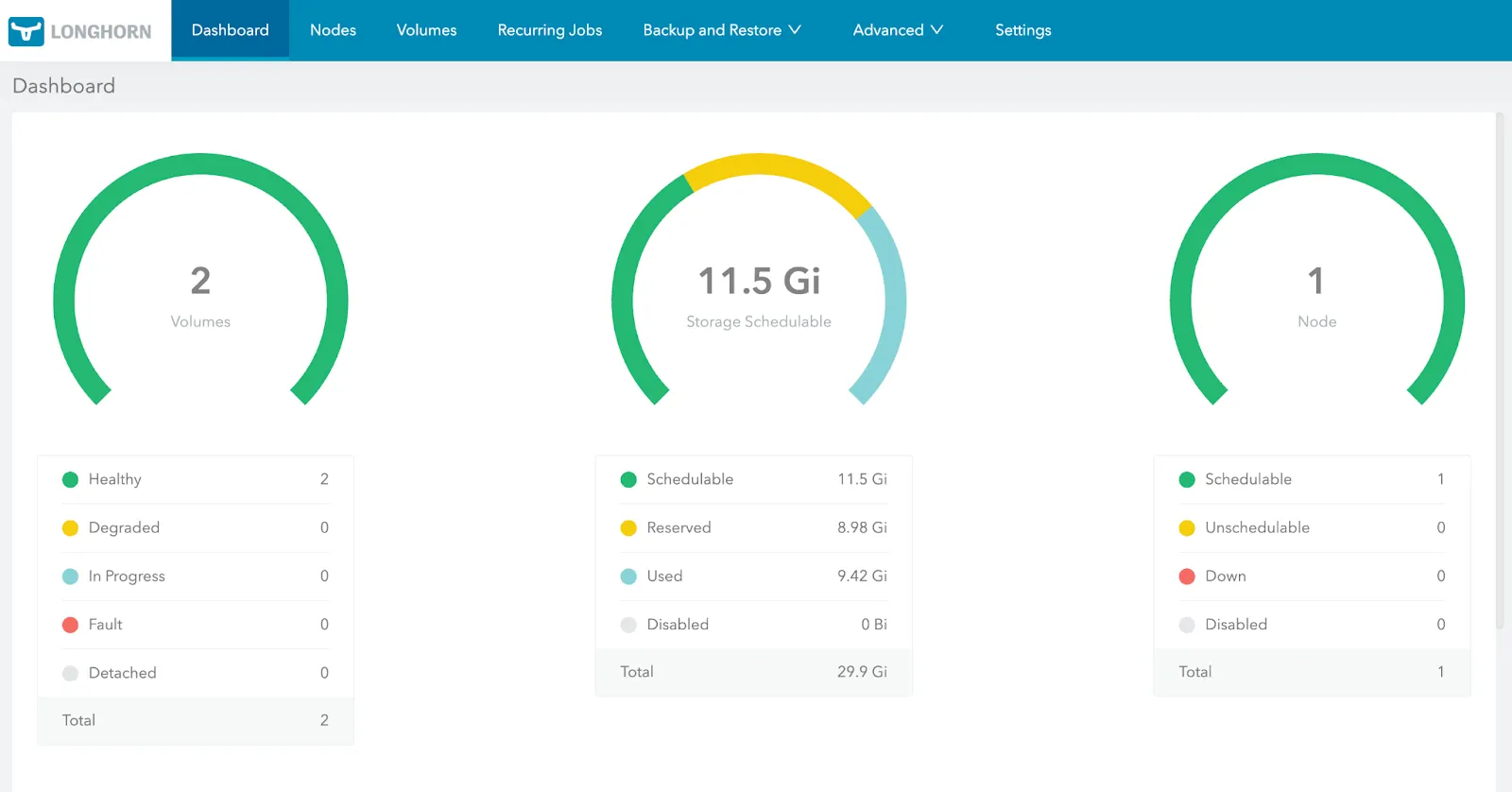

Longhorn includes a built-in web UI for visual management alongside CLI and API.This makes it easier for platform teams to manage storage, monitor health, and perform related operations allowing teams an additional interface option for storage operations that complements kubectl based workflows.

Note: To access the UI,you need to set up an ingress controller and enable authentication which is not enabled by default. You can refer to these steps for ingress and authentication setup.

Get the Longhorn UI’s service address

kubectl -n longhorn-system get svc

NAME TYPE CLUSTER-IP EXTERNAL-IP PORT(S) AGE

longhorn-backend ClusterIP 10.20.248.250 <none> 9500/TCP 58m

longhorn-frontend ClusterIP 10.20.245.110 <none> 80/TCP 58mNavigate to the IP of longhorn-frontend in your browser.

Longhorn dashboard. Source: Longhorn documentation.

Longhorn’s UI advantages:

- Built-in and ready-to-use: No separate installation, automatically deployed with Longhorn

- Comprehensive & Centralized management: Volume creation/deletion, snapshots, backups, node/disk management, recurring jobs all in one place

- Storage visibility: Real-time visualization of disk usage, replica health, volume status

- Operations-friendly: Platform teams can manage storage without memorizing kubectl commands

Managing Data Protection and Resilience

Longhorn implements data protection as distinct layers, each of them addressing different failure domains. Synchronous replication handles infrastructure failures instantly while snapshots enable rollbacks from application errors within the same cluster and backups store data externally, surviving complete cluster destruction but requiring longer recovery times.

Understanding these mechanisms in order clarifies when to use each approach. In the following sections, we look at each mechanism’s technical implementation, configuration requirements, and appropriate use cases.

Snapshots and Backups

Snapshots

Snapshots in Longhorn are crash-consistent point-in-time copies stored locally within the cluster. When you create a snapshot, Longhorn issues a filesystem sync to flush pending writes, then captures the volume state. You can either use the Longhorn dashboard to create a snapshot or use a custom resource with kubectl.

#Prepare the manifest

apiVersion: longhorn.io/v1beta2

kind: Snapshot

metadata:

name: staging-longhorn-snapshot

namespace: longhorn-system

spec:

volume: pvc-2345674-48hp-49fd-8294h-54bc5be639de # replace with your actual Longhorn volume name

createSnapshot: true

#Apply the manifest

kubectl apply -f longhorn-snapshot.yaml

snapshot.longhorn.io/longhorn-test-snapshot createdThe implementation uses copy-on-write organized as a chain where the oldest snapshot serves as the base layer, with newer snapshots storing only changed blocks. This means snapshot creation is instantaneous since Longhorn doesn’t copy data, it simply marks the current state and tracks future changes.

Snapshots are stored as part of each volume replica. With three replicas, each maintains its own snapshot chain, providing redundancy but also tripling storage consumption. Longhorn also allows configuring snapshot limits including maximum count [SnapshotMaxCount] and the size [SnapshotMaxSize] to prevent exhausting disk space.

The key advantage of snapshots is the recovery speed. Reverting a database after a failed migration is faster because snapshots are stored locally within the cluster. Longhorn just remounts the volume at the snapshot point without network transfers. However, snapshots are vulnerable to cluster-wide failures since they exist on the same infrastructure as the volume data.

Backups

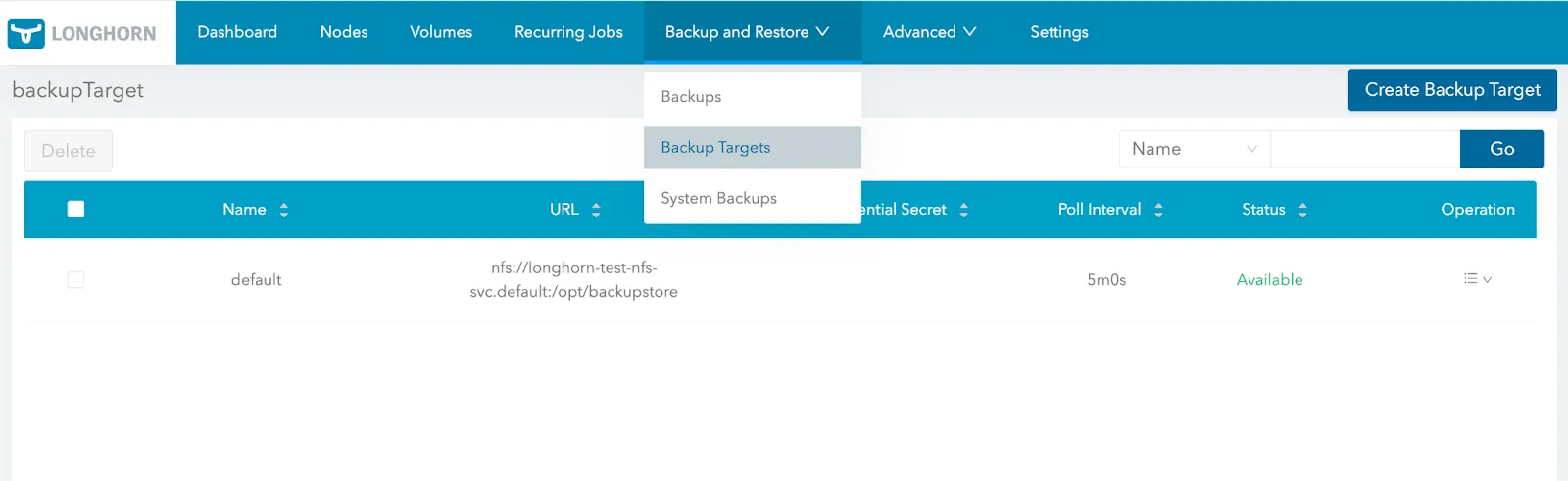

Backups store data outside the Kubernetes cluster in external targets (S3-compatible object storage or NFSv4 servers). This external storage survives scenarios where the entire cluster becomes unavailable due to datacenter failures or cascading infrastructure problems.

The default backup target (default) is automatically created during the first install. You can also set the default backup target during or after the installation using either Helm or a manifest YAML file(longhorn.yaml).

Backup creation involves two steps:

- It creates a snapshot to establish a consistent point in time;

- Then it uploads the snapshot data to the configured backup target.

After the initial full backup, Longhorn performs incremental backups. The data is compressed and deduplicated at the block level, so identical blocks across multiple backups are stored only once. Despite this optimization, each backup is stored as an independent object, allowing deletion of old backups without affecting newer ones.

Backups require configuring a backup target in Longhorn’s global settings with credentials stored as Kubernetes secrets. Once configured, any volume can create backups to this target. The backup target becomes critical infrastructure – if unavailable, neither new backups nor disaster recovery volume synchronization can proceed.

Configuring backup targets in Longhorn dashboard. Source: Longhorn documentation.

Recovery from backups takes significantly longer than snapshots because data transfers from the external target back to the cluster. For instance, a 500GB volume restored from S3 over 1 Gbps may take approximately 70 minutes. This is the fundamental trade-off – backups provide protection against cluster-wide failures but require longer recovery times.

Creating snapshots and backups manually doesn’t scale for production workloads that need consistent protection. Longhorn addresses this through recurring jobs that automate snapshot and backup creation using cron expressions. Jobs can be attached to individual volumes or volume groups through StorageClass parameters, implementing different protection policies for different workload.

Key Differences:

- Storage location: Snapshots on local cluster nodes; backups in external S3/NFS targets

- Failure protection: Snapshots vulnerable to cluster failures; backups survive datacenter loss

- Recovery time: Snapshots in seconds; backups in minutes to hours

- Capacity impact: Snapshots multiply by replica count; backups stored once with deduplication

- Use case: Snapshots for operational rollbacks; backups for disaster recovery

The choice between snapshots and backups depends on recovery time and failure scenarios based on your business requirements. For routine operational issues, snapshots suffice. For true disaster recovery where the entire cluster may be lost, backups are essential.

Longhorn’s volume-level snapshots and backups provide foundational protection, but enterprise applications often require coordinated backups across multiple volumes, application-level quiescing, and namespace-wide recovery capabilities. For automated, application-aware protection that orchestrates these complex requirements beyond the storage layer, teams can integrate dedicated solutions like Portworx Backup.

Disaster Recovery Strategies

The goal of disaster recovery is to minimize downtime when an entire cluster becomes unavailable. A disaster recovery plan can span from simple backup-and-restore approaches that maintain backups in external storage to sophisticated replication between clusters. While disaster recovery from backups can work, the restoration process can take hours. This recovery time is unacceptable for mission-critical workloads.

Longhorn’s DR volume feature optimizes recovery time by pre-positioning data in a secondary cluster through continuous asynchronous replication. However, this replication doesn’t happen through direct cluster-to-cluster connections. Here’s how it works:

- You set up a shared backup target that both your primary and secondary clusters use.

- The primary cluster creates regular backups to this backup target.

- The DR volume in the secondary cluster continuously polls this backup target for new backups.

- When it detects a backup, it incrementally restores the changed blocks to local replicas while being in read-only mode.

The DR volume is in a passive standby state by default. It is not mounted or accessible by any workloads, which prevents data inconsistencies. In a disaster, you activate the volume and it becomes a standard Longhorn volume read to be attached to your applications.

This architecture has important implications for understanding Longhorn’s disaster recovery capabilities. The DR volume is always behind the primary volume by the backup frequency plus the poll interval. If your primary cluster creates hourly backups and the DR volume polls every 5 minutes, the worst-case data loss scenario is 65 minutes – if a disaster occurs right after the DR volume polls and just before a scheduled backup completes.

RTO and RPO Trade-offs

Recovery Time Objective quantifies how quickly you must restore service after a failure. With traditional backup restoration, RTO depends on volume size and network bandwidth. DR volumes dramatically reduce RTO because the data already exists on local disks in the secondary cluster and the recovery takes seconds, not hours. You’re simply changing the volume state from standby to read-write.

However, this improved RTO comes with infrastructure costs. You’re maintaining an entire secondary cluster with volumes pre-provisioned and consuming disk space, even though those volumes aren’t serving active workloads. The cost calculation becomes: faster failover capability versus doubled infrastructure spend. For applications where every minute of downtime translates to significant revenue loss or regulatory impact, the trade-off favors DR volumes. For non-critical workloads, accepting longer restoration times from backups may be more economical.

The RPO calculation is straightforward: backup frequency equals maximum data loss. Hourly backups mean you can lose up to one hour of data. More frequent backups reduce RPO but increase storage costs, network bandwidth consumption, and load on the backup target. Teams must balance these factors based on their actual business requirements.

Volume-Level Limitations

A critical constraint of Longhorn’s disaster recovery is that it operates purely at the volume level without application awareness. When you create a DR volume, Longhorn has no knowledge of the application using that volume, relationships between multiple volumes serving the same application, or Kubernetes resources like ConfigMaps and Secrets that define application configuration.

This limitation becomes significant for multi-component applications. Activating DR volumes independently might result in a database data volume from 12:00 PM paired with a transaction log volume from 10:45 PM, requiring manual recovery procedures to achieve application consistency.

Longhorn’s DR is not a live data stream, it is limited by backup frequency. Because replication is asynchronous and happens via a backup target rather than synchronous across clusters. And due to this, your data loss window must match your backup interval – hourly backups mean accepting up to one hour of potential data loss.

Organizations running Tier-1 applications need to utilize synchronous Kubernetes Disaster Recovery solutions to ensure business continuity.

Thus, it’s critical to design recovery procedures that account for these volume-level constraints, test those procedures regularly under realistic conditions, and document the manual steps required to bring applications to consistent states after DR volume activation.

Performance and Scalability Considerations

Longhorn’s architecture trades raw performance for operational simplicity. Understanding these performance characteristics helps teams identify when Longhorn fits their requirements and when it doesn’t.

Resource Consumption and Overhead

Every Longhorn volume runs multiple pods across the cluster. A three-replica volume runs four pods consuming CPU, memory, and network bandwidth. The engine handles iSCSI requests, coordinates parallel writes to replicas, and manages snapshot chains. Memory consumption scales with concurrent I/O operations and snapshot chain complexity.

Network bandwidth becomes a constraint because synchronous replication requires writes to complete on all replicas before acknowledging to the application. A 1MB write with three replicas is 3x more costly from a network and write POV. High-write workloads on resource-constrained clusters will experience degraded performance, especially when large data transfers compete with application I/O.

Write latency is determined by the slowest replica. A single node with poor disk performance degrades the entire volume’s write performance. Thus the performance is constrained by the underlying node’s disk performance.

Replica Rebuilds and Operational Impact

When a node fails, Longhorn automatically rebuilds failed replicas on healthy nodes. Rebuild time scales linearly with volume size: a 100GB volume might rebuild in 10-15 minutes, while a 1TB volume takes 2-3 hours.

Rebuilds consume significant network bandwidth, disk I/O, and CPU without throttling by default. Multiple concurrent rebuilds after maintenance events can saturate cluster resources and impact application performance. This creates operational challenges especially with many large volumes, maintenance windows extend from minutes to hours as rebuild operations serialize.

Workload Suitability

Longhorn does well in situations where operational simplicity is the primary goal. For instance, edge deployments benefit from lightweight footprint and lack of external dependencies. CI/CD pipelines can use Longhorn for build artifacts and test databases. Development and staging environments gain production-like storage without enterprise complexity.

General-purpose applications like web servers, content management systems, logging infrastructure perform well because their bursty I/O patterns don’t saturate storage systems. The ability to snapshot, backup to object storage, and restore across clusters provides value despite not being the fastest option.

When to Consider Alternatives

High-IOPS databases like PostgreSQL with 10K+ queries/second or Elasticsearch with heavy indexing expose Longhorn’s performance limitations. Userspace architecture and network replication add latency to every write.

Low-latency systems like trading platforms, real-time analytics requiring sub-millisecond p99 write latency will find Longhorn insufficient. Synchronous replication means write latency includes network round-trip time to the furthest replica.

Massive scale deployments face increased operational complexity managing replica rebuilds, coordinating upgrades, and troubleshooting performance at scale.

Maintenance and Upgrades

While Longhorn provides simplicity, cluster maintenance becomes challenging, especially at scale. When you drain a node hosting Longhorn replica pods, Longhorn interprets this as replica failure and immediately starts rebuilding those replicas on other healthy nodes.

Draining faster than rebuilds complete, reduces redundancy below safe levels. For instance, Node A hosts replicas for Volume X. You drain Node A, and Longhorn starts rebuilding those replicas on Node C. Before that rebuild completes, you drain Node B – which also has replicas for Volume X. Now Volume X has two replicas rebuilding at once, leaving only one healthy replica. If Node C fails during this window, you lose Volume X entirely.

This forces sequential maintenance. Drain Node A, wait for all its replicas to rebuild – possibly hours if it hosts many large volumes – then drain Node B

Longhorn allows disabling automatic rebuilds during maintenance windows, letting you drain all nodes quickly and rebuild afterward. This shortens the maintenance window however creates a vulnerable situation – if hardware fails while rebuilds are disabled, data loss is possible. Thus production teams must choose between extended low-risk maintenance or shorter high-risk maintenance.

Enterprise Storage For Kubernetes Using Portworx

When workloads mature from development to production, teams notice the surge in complexity and encounter scenarios where Longhorn’s architecture reaches its operational boundaries. Mission critical apps with stricter performance SLAs, zero data loss requirements or complex multi-volume dependency typically need robust capabilities that expand beyond this community storage offering.

Portworx addresses these challenges through capabilities designed specifically for enterprise Kubernetes environments to support complex and demanding workloads.

- Direct Block I/O Architecture: Portworx operates through kernel modules with direct block device access that bypasses external protocols, delivering over 1 million IOPS for NVMe-backed workloads.

- Zero RPO Disaster Recovery: Synchronous replication across metro regions (<10ms latency) ensures mission-critical workloads experience zero data loss during failovers. Reduces RTO to under 60 seconds and meet even the strictest of SLAs.

- Automate Storage Workflows: Eliminate manual effort with automated and intelligent workflows for disaster recovery, capacity management, and pod placement

- Unified Data Management Platform: Consolidate storage, backup, and disaster recovery into a single solution that spans on-premises, public cloud, and hybrid environments without infrastructure lock-in.

Learn more about how Portworx compares to Longhorn.

Conclusion

Longhorn delivers cloud-native block storage with a focus on operational simplicity over raw performance. Its architecture provides multiple protection layers addressing different failure scenarios. The Longhorn dashboard coupled with a straightforward installation makes Longhorn accessible to teams without dedicated storage expertise, while features like recurring jobs and StorageClass integration enable production-grade automation.

Having said that, the trade-offs are clear. Replica rebuilds consume cluster resources and extend the duration of maintenance windows. Applications demanding sub-millisecond write latency or extreme IOPS need specialized solutions. However, for edge deployments, CI/CD environments, development clusters, and general-purpose workloads where operational ease matters more than peak operational performance, Longhorn provides reliable persistent storage without external dependencies or complex infrastructure.

For teams looking for simple, portable Kubernetes storage without the complexity of traditional SAN/NAS systems, Longhorn delivers practical, production-ready block storage that integrates naturally with cloud-native workflows.

Frequently Asked Questions about Longhorn Storage

Q: Is Longhorn storage production-ready for databases?

Longhorn is widely used in production for general-purpose workloads, CI/CD pipelines, and edge computing. However, for high-performance databases (like PostgreSQL, Cassandra, or MongoDB) with high transaction rates (IOPS), you should carefully evaluate the performance.

Because Longhorn runs in user space and uses iSCSI for replication, there can be latency overhead compared to kernel-based solutions. For mission-critical databases requiring millions of IOPS and low latency, enterprise-grade solutions like Portworx are often preferred for their kernel-optimized data paths.

Q: Does Longhorn support ReadWriteMany (RWX) volumes?

Yes, Longhorn supports RWX volumes. It achieves this by provisioning a “Share Manager” pod that runs an NFS server to export the volume to multiple nodes.

Note: Since all traffic is funneled through this single NFS pod (creates a dedicated Share Manager volume pod per RWX volume in use), it can become a performance bottleneck for write-heavy workloads. If your application requires high-performance shared storage, ensure you monitor the Share Manager’s resource usage.

Q: Can I achieve Zero RPO (No Data Loss) with Longhorn Disaster Recovery?

Longhorn’s Disaster Recovery (DR) volumes use asynchronous replication based on backups to S3 or NFS. This means your Recovery Point Objective (RPO) is tied to your backup frequency. If you back up every hour, you risk losing up to one hour of data during a disaster.

Pro Tip: For banking, healthcare, or core business applications that require Zero RPO (synchronous replication across clusters), you will need a solution capable of synchronous Metro DR, such as Portworx Disaster Recovery.

Q: What is the difference between a Longhorn Snapshot and a Backup?

- Snapshots are local to the cluster and stored on the same disk as the volume data. They are instant but do not protect you if the physical disk or node fails completely.

- Backups are stored off-site (e.g., in AWS S3 or an NFS server). They are deduplicated and compressed.

- Backups are stored off site (NFS, SMB/CIFS, Azure Blob Storage, and S3 compatible) and they are incremental, block-based (2 MB), compressed, and can reuse unchanged blocks across backups of the same volume (dedupe-like behavior).

- Best Practice: Always configure RecurringJobs to push backups off-site for true disaster recovery.

Q: How does Longhorn handle node failures?

If a node fails, Longhorn automatically detects that the replicas on that node are unavailable. If you have configured a replica count of 3 (the default), Longhorn will continue serving data from the remaining two healthy replicas. It will then automatically provision a new replica on a different healthy node to restore the cluster to full health.

Q: Is Longhorn completely free?

Yes, Longhorn is 100% open-source software (CNCF Incubating project). However, “free” refers to the license cost. You must still account for the cost of:

- Compute Resources: Longhorn consumes CPU and RAM on your worker nodes.

- Management Overhead: Your DevOps team is responsible for upgrades, troubleshooting, and maintenance.

- Support: Enterprise support typically requires a paid contract with SUSE or a move to a supported platform like Portworx.