This blog is part of Demystifying Kubernetes for the VMware Admin, a 10-part blog series that gives VMware admins a clear roadmap into Kubernetes. The series connects familiar VMware concepts to Kubernetes—covering compute, storage, networking, security, operations, and more—so teams can modernize with confidence and plan for what comes next.

Storage is the concern that keeps VMware administrators up at night when they think about Kubernetes. You spent years building a reliable storage infrastructure. vSAN aggregates local disks into shared datastores. Storage policies enforce protection levels. Snapshots and replication protect your data. Everything works because the stack is integrated and the operational model is proven.

Kubernetes handles storage differently. Containers are ephemeral by default. When a pod restarts, its local filesystem disappears. This design works well for stateless web frontends and API services. It falls apart the moment you need a database, a message queue, or any application that writes data to disk.

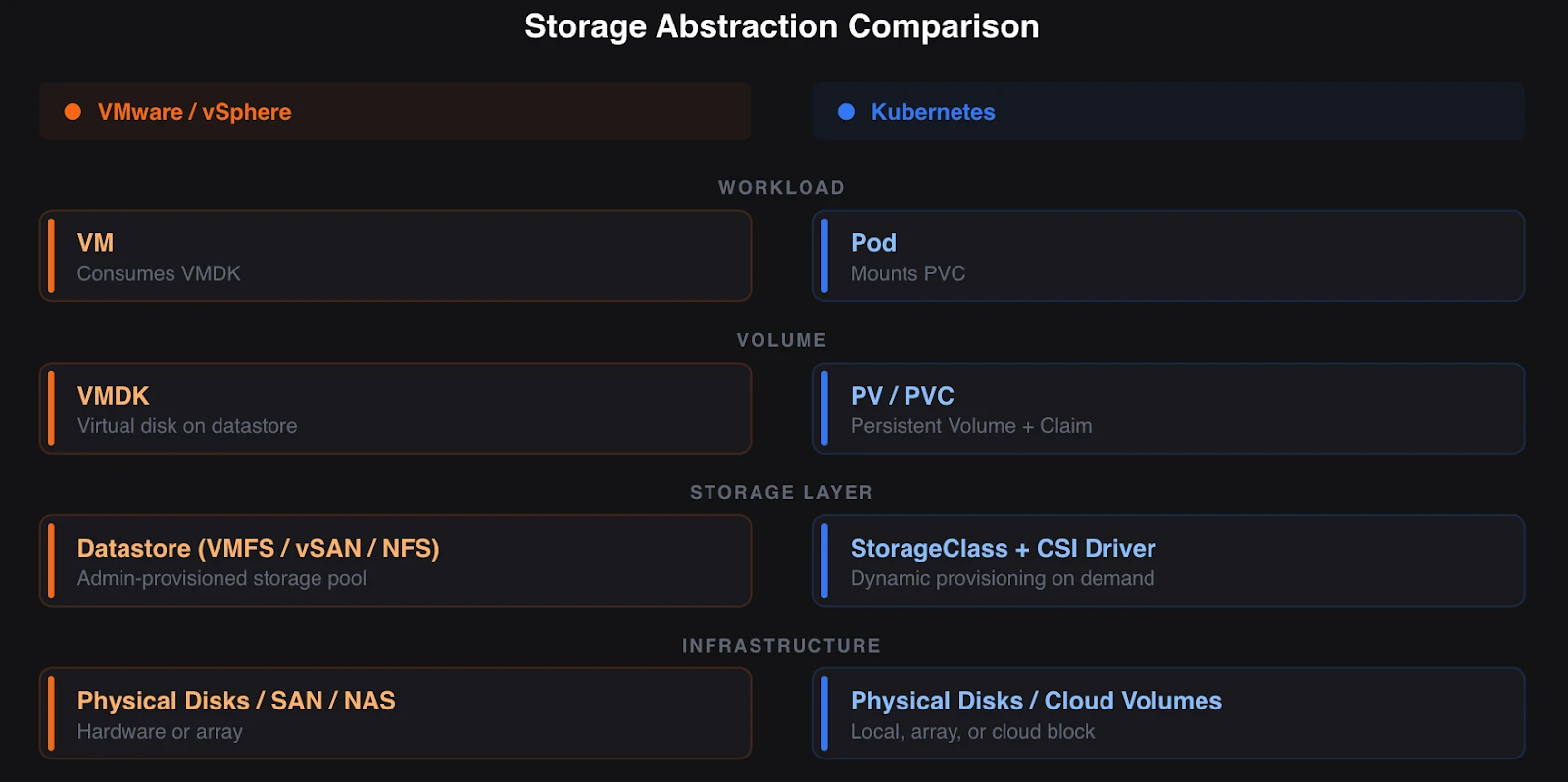

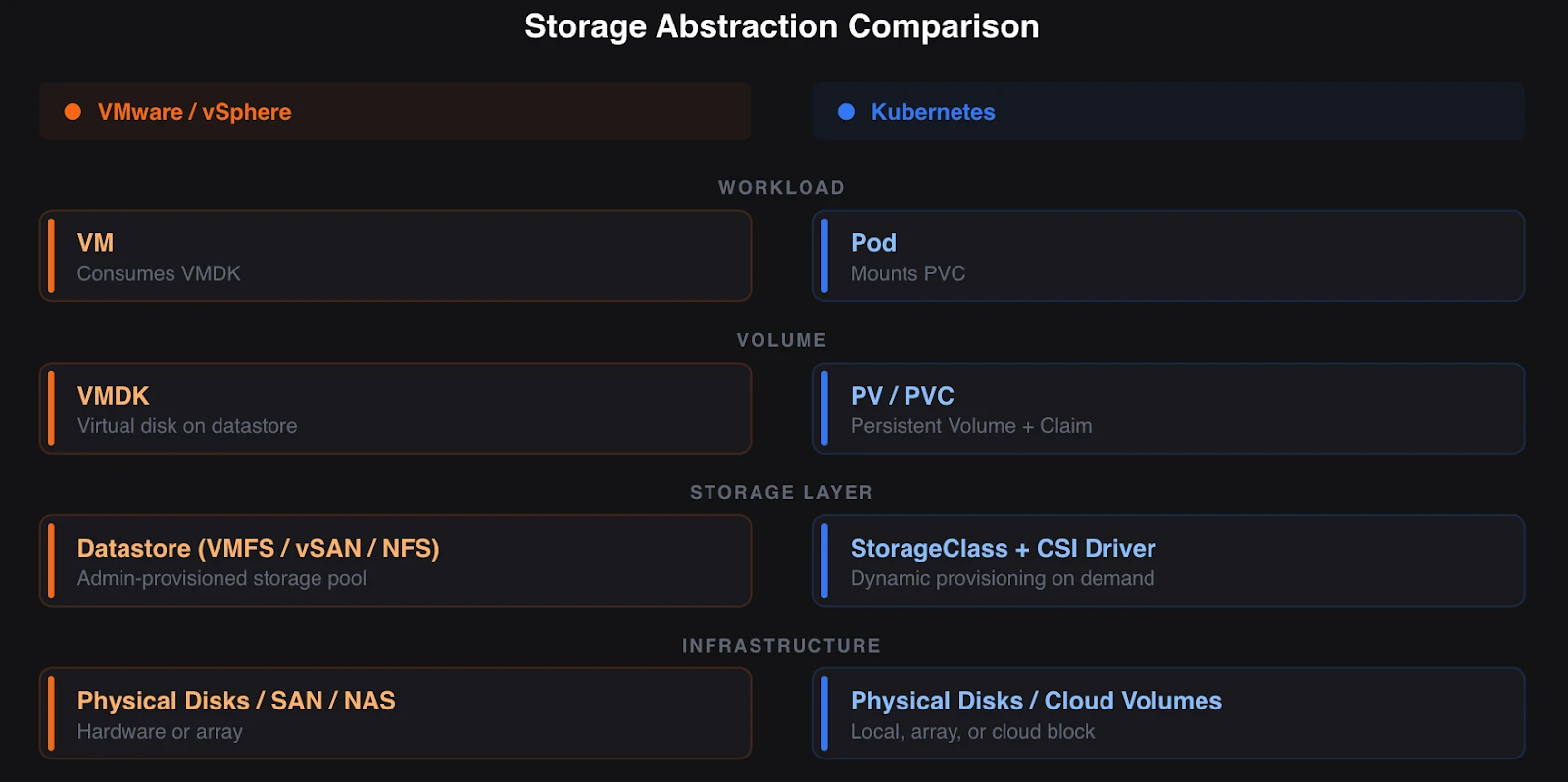

The good news: Kubernetes has a mature storage framework that maps to concepts you already know. Datastores become persistent volumes. Storage policies become storage classes. vSAN becomes a software-defined storage backend that exposes capacity through a standard interface. The abstractions are different. The goals are identical.

This chapter walks through each VMware storage concept and shows you where it lands in the Kubernetes world.

Datastores and VMFS vs Persistent Volumes and Claims

In vSphere, a datastore is an abstraction over physical storage. VMFS datastores sit on top of block storage from a SAN. vSAN datastores aggregate local disks from ESXi hosts into a distributed storage pool. NFS datastores present file-based storage from a NAS appliance. VMs consume storage from these datastores through virtual disks (VMDKs) without knowing or caring about the underlying hardware.

Kubernetes uses a two-part abstraction: Persistent Volumes (PVs) and Persistent Volume Claims (PVCs).

A PV represents a storage resource in the cluster. Think of it as the Kubernetes equivalent of a datastore LUN or a vSAN object. A PV has a specific capacity, access mode, and backend type. The cluster administrator or a storage provisioner creates PVs to make storage available.

A PVC is a storage request made by an application. Think of it as the equivalent of creating a VMDK on a datastore. A developer writes a PVC that says, “I need 50GB of fast block storage.”

Kubernetes finds a matching PV and binds the two together. The application gets its storage without knowing which backend provided it.

This separation of concerns is intentional. Cluster administrators manage PVs and storage backends. Application developers create PVCs. Neither needs to understand the other’s domain in detail. In vSphere, a VM administrator works with datastores that a storage administrator provisioned. The model is the same.

The critical difference lies in dynamic provisioning of volumes in Kubernetes. In vSphere, datastores exist before VMs request storage. Someone creates the datastore, configures VMFS, and presents it to the cluster. Kubernetes supports this static provisioning model, but most production environments use dynamic provisioning instead. When a PVC is created, and no existing PV matches it, Kubernetes tells the storage backend to create one on the fly. The PV appears, binds to the PVC, and the pod gets its volume. No manual intervention required.

Dynamic provisioning changes the operational model. You stop pre-creating storage and start defining policies that describe what types of storage are available. This is where storage classes come in.

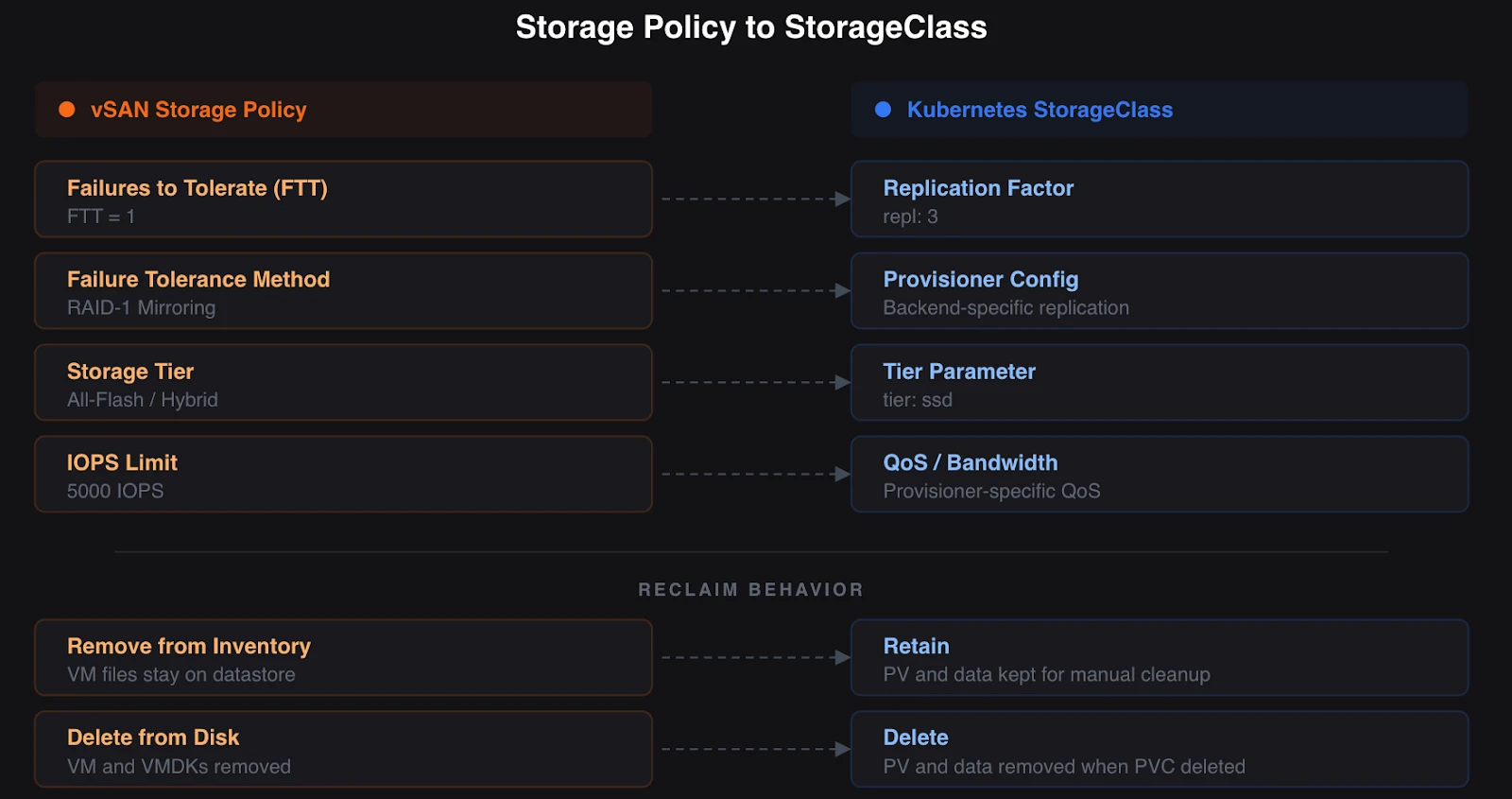

Storage Policies vs Storage Classes

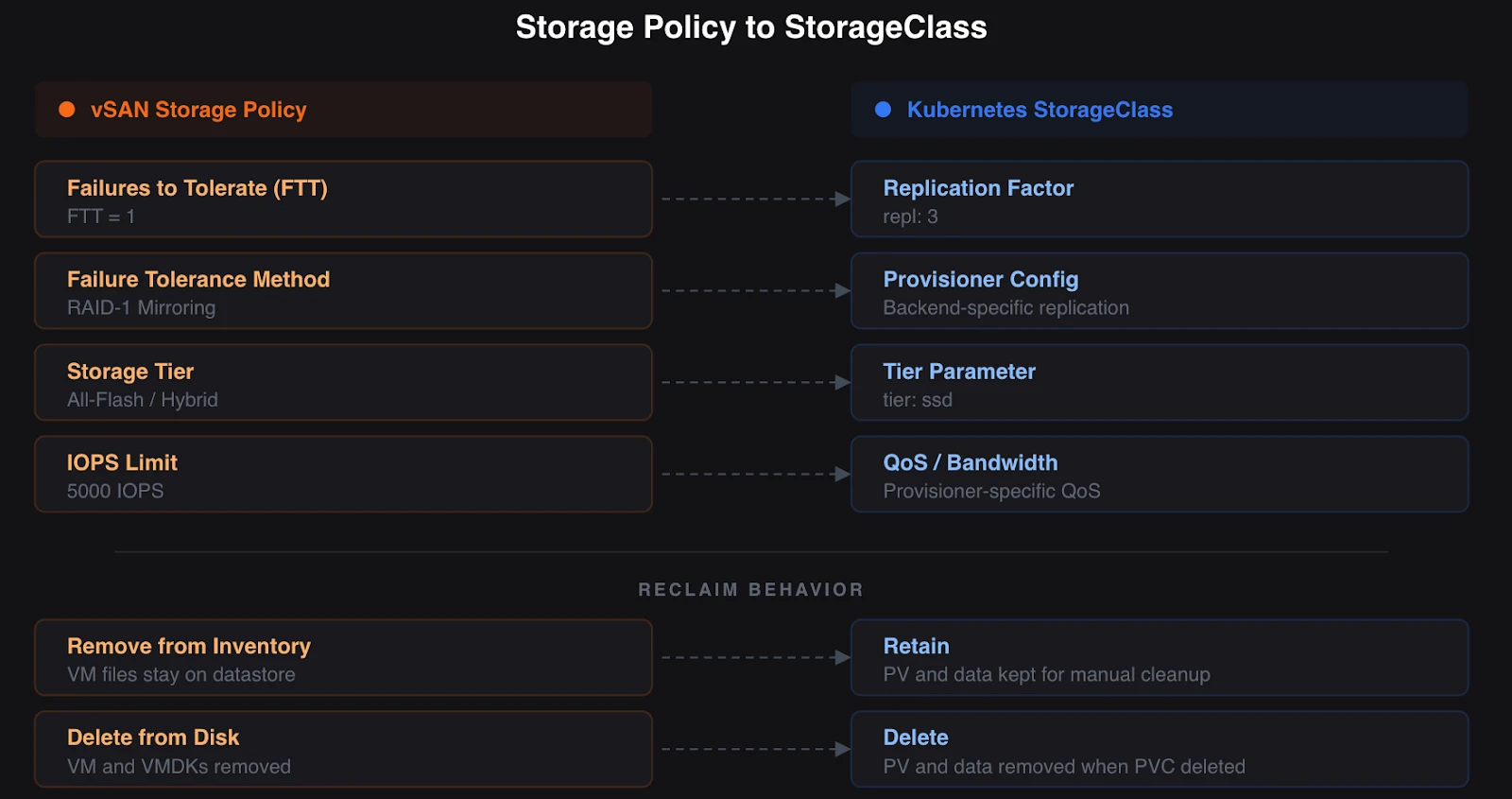

In vSAN, storage policies define the characteristics of your storage. You create a policy that specifies the number of failures to tolerate (FTT), the failure tolerance method (RAID-1 mirroring or RAID-5/6 erasure coding), stripe width, and IOPS limits. When you provision a VM, you assign a storage policy. vSAN ensures the data meets those requirements.

VCF 9.0 extends this model with Storage Policy Based Management (SPBM), which provides a unified policy framework across vSAN, VMFS, and NFS datastores. You define what you need. The platform delivers it.

Kubernetes storage classes serve the same purpose. A StorageClass is a declarative object that defines a type of storage available in the cluster. It specifies which provisioner creates the volumes, which parameters to use, and the reclaim policy that applies when the PVC is deleted.

Here is a simplified comparison.

In vSAN, you create a storage policy with FTT=1, RAID-1 mirroring, and assign it to a VM. The VM gets replicated storage that survives a single host failure.

In Kubernetes, you create a StorageClass that points to a storage backend, specifies a replication factor of 3 and a fast SSD tier, and sets the reclaim policy to delete. When a PVC references this StorageClass, the backend provisions a volume that matches those parameters.

The mapping is direct. Storage policy name becomes StorageClass name. Protection parameters become provisioner-specific parameters. Assign-on-create works the same way. The PVC references a StorageClass the way a VM references a storage policy.

One key aspect for operations is reclaim policies. In vSphere, choosing “Remove from Inventory” retains all VM files on the datastore, including VMDKs. “Delete from Disk” permanently removes the VM and its files. Kubernetes gives you two options. “Delete” removes the PV and its data when the PVC is deleted. “Retain” keeps the PV and data for manual cleanup. Choose based on your data lifecycle requirements. Production databases should use “Retain” to prevent accidental data loss.

Storage classes also support volume binding modes. “Immediate” creates the volume immediately when the PVC is created. “WaitForFirstConsumer” delays volume creation until a pod needs it. The second mode is important for topology-aware storage, where the volume needs to be created on the same node or in the same fault domain, such as a zone, as the pod that will use it.

The Container Storage Interface (CSI)

In vSphere, storage integration happens through VAAI (vStorage APIs for Array Integration) and VASA (vStorage APIs for Storage Awareness). These APIs enable vSphere to communicate with storage arrays to offload operations such as cloning, snapshotting, and thin provisioning. The storage vendor writes a VAAI/VASA provider. vSphere talks to the provider. The array does the work.

Kubernetes uses the Container Storage Interface (CSI) to achieve the same goal. CSI is an open standard that defines how container orchestrators interact with storage systems. A storage vendor writes a CSI driver. Kubernetes talks to the driver. The storage system does the work.

Before CSI, Kubernetes storage drivers were compiled into the Kubernetes binary itself. Adding support for a new storage system required changes to the core Kubernetes codebase. CSI moved storage drivers out of the core and into independent, pluggable components. Storage vendors now ship their own CSI drivers and update them on their own release cadence.

This is similar to how VMware moved from in-box drivers to the modern VAAI plugin model. The storage vendor owns the integration layer. The platform provides the interface. Neither needs to ship on the other’s schedule.

Every major storage vendor provides a CSI driver. Cloud providers ship CSI drivers for their managed block and file storage services. Pure Storage, NetApp, Dell, HPE, and dozens of others provide CSI drivers for their hardware arrays. Software-defined storage platforms like Portworx by Pure Storage, Rook (for Ceph), and Longhorn include CSI drivers as part of their deployment.

A CSI driver handles volume creation, deletion, attachment, detachment, mounting, snapshotting, cloning, expansion, and health monitoring. The driver runs as pods in your Kubernetes cluster. When Kubernetes needs a storage operation, it calls the CSI driver through gRPC. The driver translates the request into the format required by the backend storage system. One important distinction: hardware vendor CSI drivers are tied to a specific array. A NetApp CSI driver works only with NetApp storage. A Dell CSI driver works only with Dell arrays. The capabilities each driver exposes vary by vendor and version. Some support snapshots and cloning. Others do not. SDS platforms like Portworx take a different approach. Portworx provides its own CSI driver that delivers a consistent set of data services across any backend, whether the underlying storage is an enterprise array, local disks, or cloud block storage. This is closer to how vSAN works, where uniform storage services are independent of hardware.

For VMware professionals, CSI replaces the combination of VAAI, VASA, and the vSphere storage stack’s native integrations. The difference is that CSI is vendor-neutral and works with all Kubernetes distributions. Your CSI driver works the same way on Red Hat OpenShift, Rancher, EKS, AKS, and GKE.

Software-Defined Storage in Kubernetes

vSAN is software-defined storage purpose-built for vSphere. It aggregates local disks from ESXi hosts into a distributed storage pool, replicates data according to storage policies, and delivers enterprise data services such as snapshots, encryption, and compression. vSAN ESA (introduced with vSAN 8) is optimized for modern NVMe hardware, delivering improved efficiency, scalability, and performance. VCF 9.0 (GA June 17, 2025) builds on ESA with features such as vSAN-to-vSAN replication for disaster recovery and disaggregated storage clusters that separate compute from storage.

Kubernetes does not ship with a built-in storage layer. You choose a software-defined storage platform that runs on top of your cluster. Several mature options exist, each with different strengths.

Portworx by Pure Storage is a Kubernetes data services platform built for enterprise production environments. Portworx Enterprise provides persistent storage, high availability across availability zones, automated data placement, and encryption. Portworx runs on any infrastructure: bare metal, cloud VMs, or enterprise storage arrays from Pure Storage and others. For organizations running KubeVirt to bridge VMs and containers (as covered in Part 2), Portworx provides unified storage and data management across both workload types. It supports ReadWriteMany block storage for KubeVirt VMs, synchronized disaster recovery with zero data loss (zero RPO), and file-level backups for Linux VMs on Kubernetes.

Rook is a CNCF Graduated project that orchestrates Ceph storage on Kubernetes. Ceph is a distributed storage system that provides block, file, and object storage. Rook deploys Ceph as a Kubernetes-native operator that manages the Ceph cluster lifecycle through custom resources. Choose Rook when you need multi-protocol storage (block, file, and S3-compatible object), you run on bare metal with local disks, and you want a fully open-source stack. Rook requires significant operational investment. Ceph is capable but demands expertise to tune and maintain at scale.

Longhorn is a CNCF Incubating project maintained by SUSE. Longhorn provides distributed block storage using a lightweight, microservices-based architecture. Each volume gets its own dedicated storage controller, which simplifies management and isolates failures. Longhorn includes built-in backup to S3-compatible storage, incremental snapshots, and a web-based management UI. Choose Longhorn when you want simple, easy-to-operate storage for general-purpose workloads, and you do not need the complexity of a full distributed storage system like Ceph.

For VMware professionals evaluating these options, think about it this way. vSAN is a single, integrated solution from one vendor. Kubernetes storage gives you a choice. That choice comes with a tradeoff: you are responsible for selecting, deploying, and maintaining the storage platform. Enterprise platforms like Portworx reduce that burden with automation, support contracts, and proven integrations across distributions.

How Data Services Translate

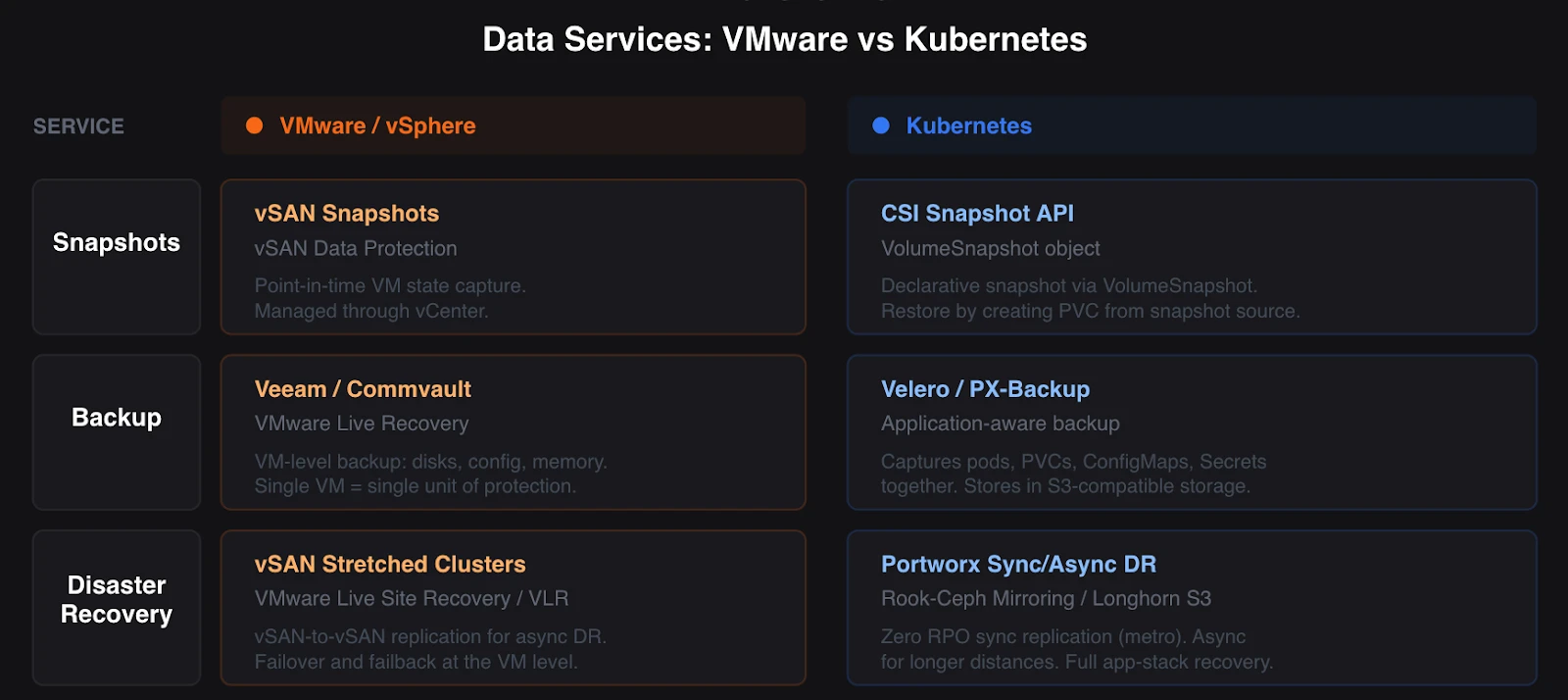

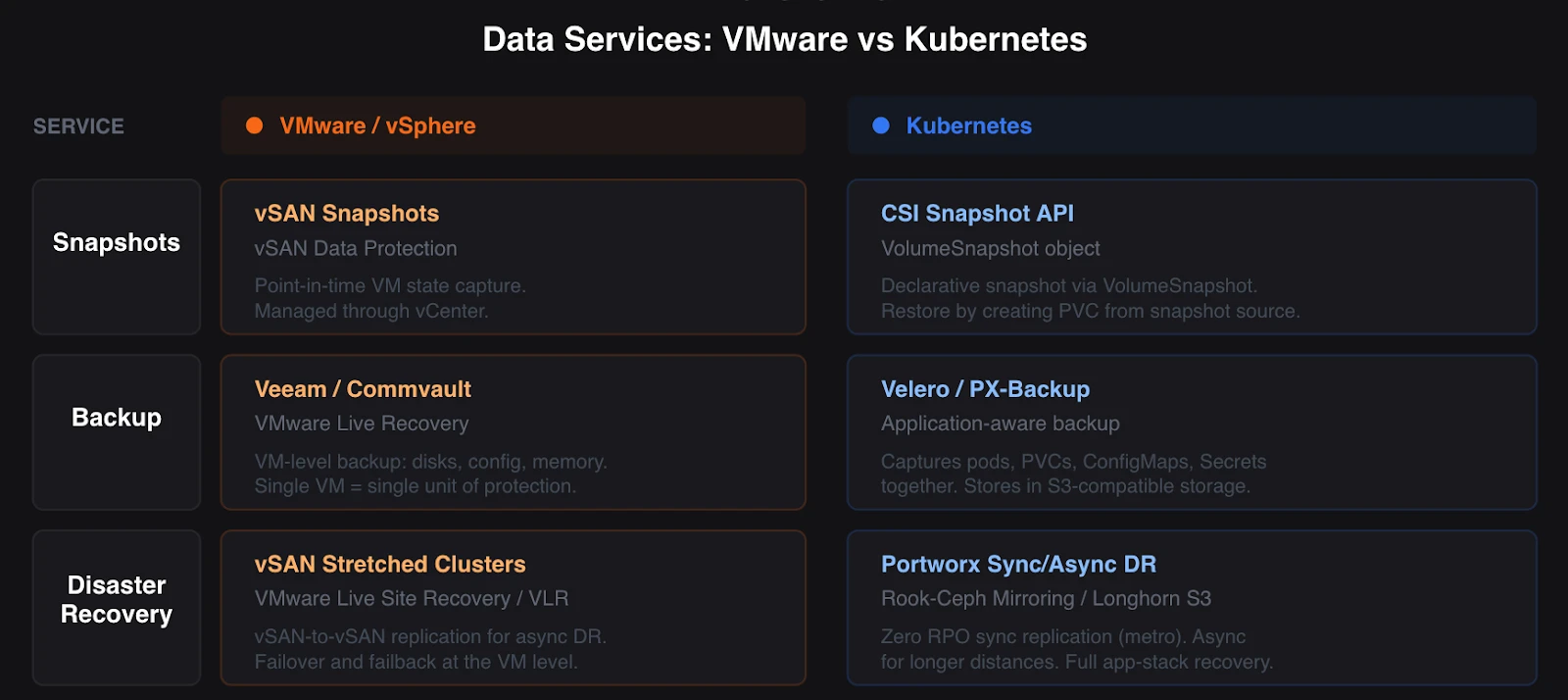

Storage is more than capacity allocation. Your vSphere environment provides snapshots, backup, replication, and disaster recovery as integrated services. These capabilities exist in Kubernetes, but they work differently.

Snapshots: vSAN snapshots capture VM state at a point in time. Kubernetes supports volume snapshots through the CSI Snapshot API. You create a VolumeSnapshot object that references a PVC. The CSI driver creates a point-in-time copy on the backend. You restore from a snapshot by creating a new PVC that references the VolumeSnapshot as its data source. The workflow is declarative. You define what you want. The system creates it.

Not all CSI drivers support snapshots. Check your storage platform’s documentation. Portworx, Rook-Ceph, and Longhorn all support CSI snapshots. Cloud provider CSI drivers for EBS, Azure Disk, and GCE Persistent Disk also support these storage types.

Backup: In vSphere, you back up VMs using tools like Veeam, Commvault, or VMware Live Recovery. VMware Live Recovery combines VMware Live Site Recovery (formerly Site Recovery Manager) and VMware Live Cyber Recovery (formerly VMware Cloud Disaster Recovery). These tools capture VM state, including disks, configuration, and memory if needed.

Kubernetes backup requires a different approach. A Kubernetes application is not a single VM. It is a collection of pods, PVCs, ConfigMaps, Secrets, and custom resources spread across multiple nodes. Backing up a single volume is not enough. You need application-consistent backup that captures all components together.

Velero (an open-source project from VMware) is the most widely adopted Kubernetes backup tool. Velero backs up both Kubernetes resources (the YAML definitions) and persistent volume data. It stores backups in S3-compatible object storage and supports scheduled backups, retention policies, and cross-cluster restores. Portworx provides its own backup solution (PX-Backup) that integrates with its storage platform for application-aware backups across Kubernetes clusters.

Disaster Recovery: vSphere provides DR through vSAN stretched clusters, VMware Live Recovery, and array-based replication. VCF 9.0 introduces vSAN-to-vSAN replication for asynchronous DR across sites.

Kubernetes DR for workloads follows similar patterns. Portworx supports synchronous replication for zero RPO across metro distances and asynchronous replication for longer distances. Rook-Ceph supports Ceph’s native mirroring for cross-cluster replication. Longhorn provides a built-in disaster recovery mechanism through backup and restore from S3 storage.

The fundamental difference: Kubernetes DR must account for the entire application stack, not a single VM. Replicating volumes is necessary but not sufficient. The Kubernetes resources, network configuration, and application state must be recoverable at the target site. Enterprise platforms like Portworx address this by providing application-aware DR that replicates both data and metadata.

What This Means for Your Operations

The storage paradigm shift from vSAN to Kubernetes is less about new technology and more about new workflows.

You stop provisioning individual datastores and start defining storage classes that describe available storage tiers. You stop manually creating VMDKs and let dynamic provisioning handle volume lifecycle. You stop relying on a single integrated stack and start evaluating storage platforms that fit your requirements.

The concepts transfer directly. Storage policies map to storage classes. Datastores map to persistent volumes. VAAI/VASA map to CSI. vSAN maps to your chosen software-defined storage backend. Snapshots, backup, and DR exist in both worlds, though the Kubernetes versions require application-aware thinking rather than VM-level operations.

Your vSAN expertise gives you a strong foundation. You understand replication factors, failure domains, storage tiering, and data protection. These concepts apply directly to Kubernetes storage platforms. The vocabulary changes. The engineering principles stay the same.

Part 6 examines networking. You will learn how NSX concepts translate to CNI plugins, how load balancing works with Kubernetes Services and Ingress controllers, and how network policies provide the micro-segmentation you rely on today.

Demystifying Kubernetes – Blog series