This blog is part of Demystifying Kubernetes for the VMware Admin, a 10-part blog series that gives VMware admins a clear roadmap into Kubernetes. The series connects familiar VMware concepts to Kubernetes—covering compute, storage, networking, security, operations, and more—so teams can modernize with confidence and plan for what comes next.

You spent years building a reliable VM infrastructure. Your applications run on VMs. Your teams understand VMs. Your monitoring, backup, and security tools integrate with VMs. Nobody expects you to abandon all of that overnight.

Adopting Kubernetes doesn’t mean abandoning virtualization entirely. You don’t need to containerize every workload before progressing. There’s a transition path that connects the VM environment you’re familiar with to the container ecosystem you’re exploring.

That bridge is KubeVirt.

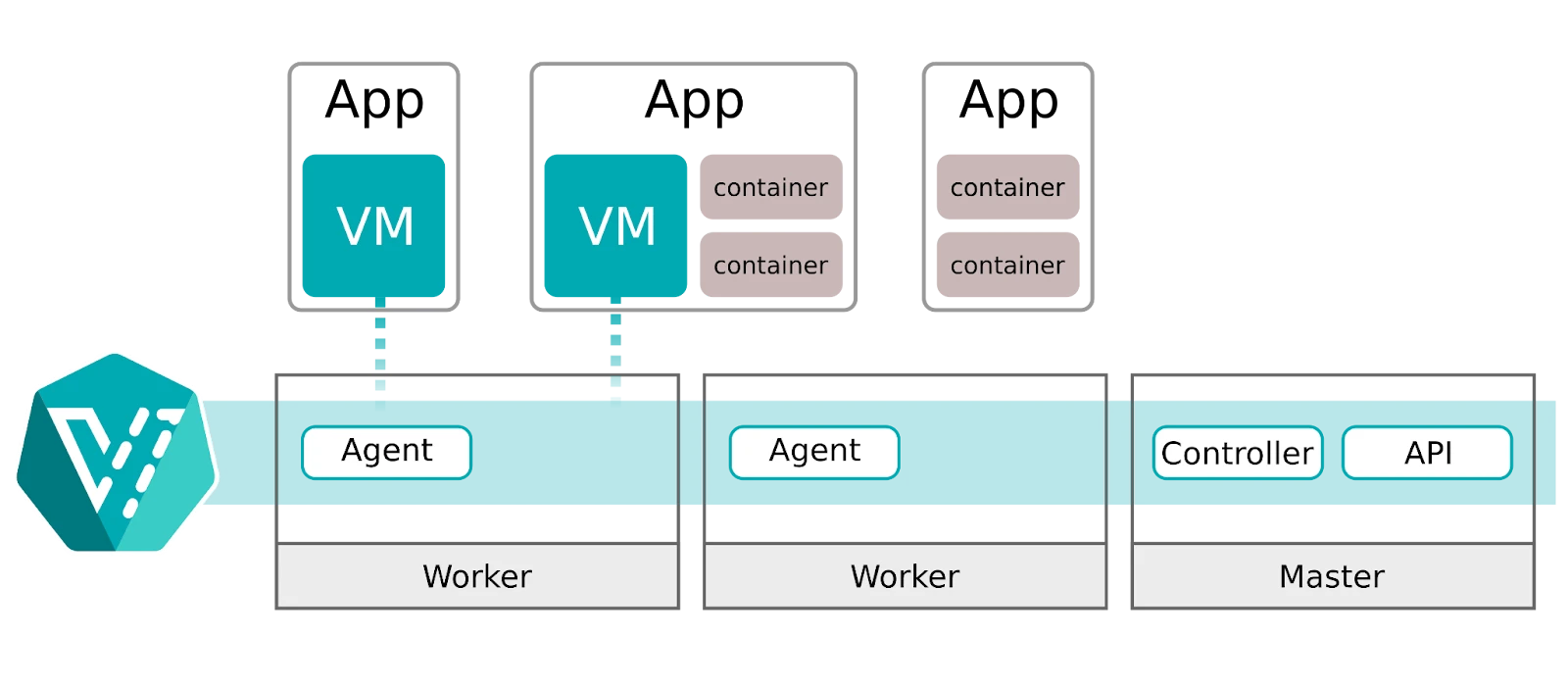

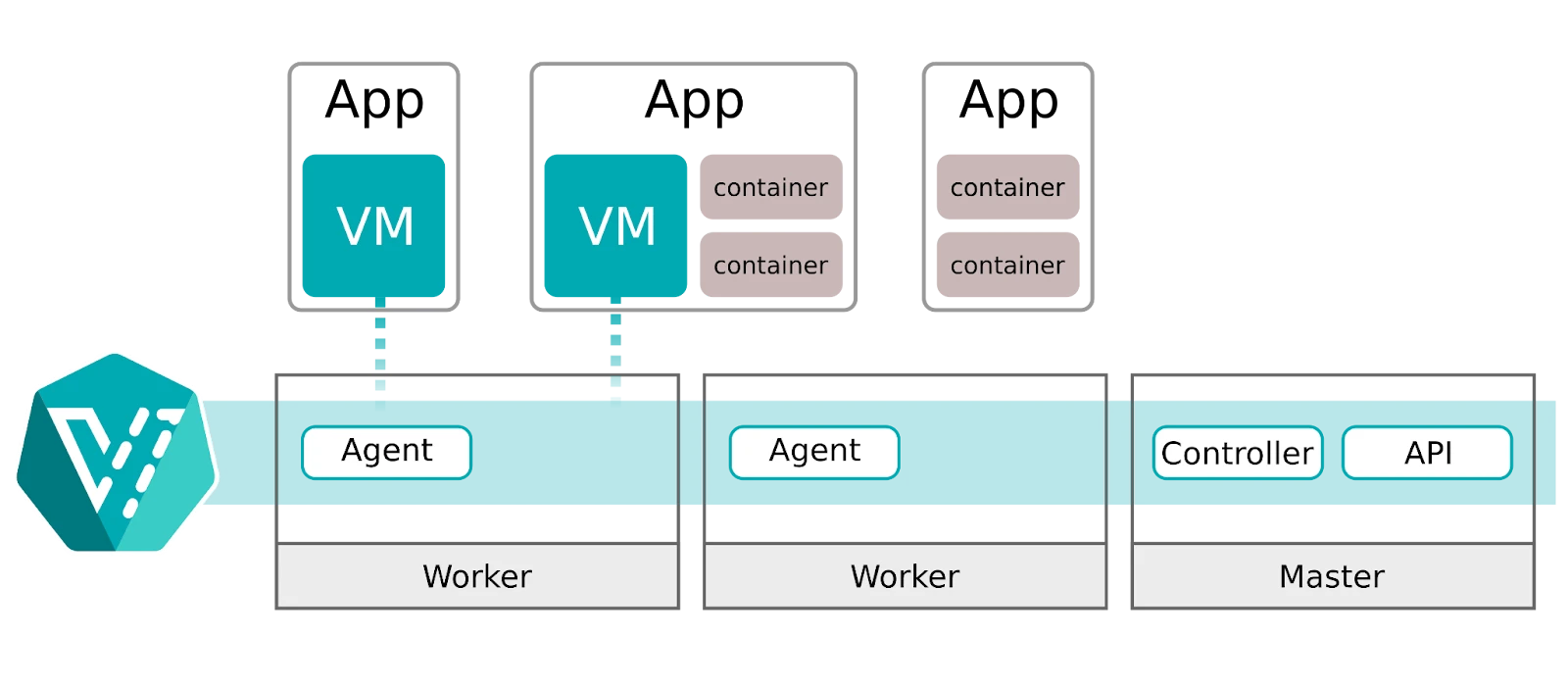

KubeVirt extends Kubernetes to run virtual machines as first-class workloads alongside containers. Your existing VMs run inside the same platform that hosts your new containerized applications. One control plane. One set of tools. One operational model. Two workload types.

This matters because real migration takes years. You have legacy applications that nobody wants to refactor. You have commercial software that only ships as VM images. You have workloads where containers make no sense today and might never make sense. KubeVirt lets you move forward without leaving these workloads behind.

Why KubeVirt Exists

Kubernetes was designed for containers. The original architects assumed applications would be stateless, ephemeral, and containerized. Pods run containers. Containers package applications. The model works for microservices, web frontends, and modern applications built from the ground up.

Enterprises operate differently. Most organizations run thousands of VM workloads accumulated over 15 years of VMware deployments. These include database servers, Microsoft Windows applications, legacy middleware, and commercial software packages. These workloads remain the backbone of enterprise IT. They generate revenue. They support business operations. Telling a CFO that migration requires rewriting every application is not a conversation anyone is going to have successfully.

The industry recognized this gap. Red Hat, Intel, and other vendors collaborated to create KubeVirt under the Cloud Native Computing Foundation. The project launched in 2017 and reached general availability in subsequent years. Production deployments now run at scale across multiple industries.

KubeVirt solves a practical problem. Organizations want Kubernetes benefits without abandoning their existing VM investments. They want one platform to manage instead of two. They want operational consistency across workload types. They want a transition path that respects their current reality while enabling their future goals.

How KubeVirt Works

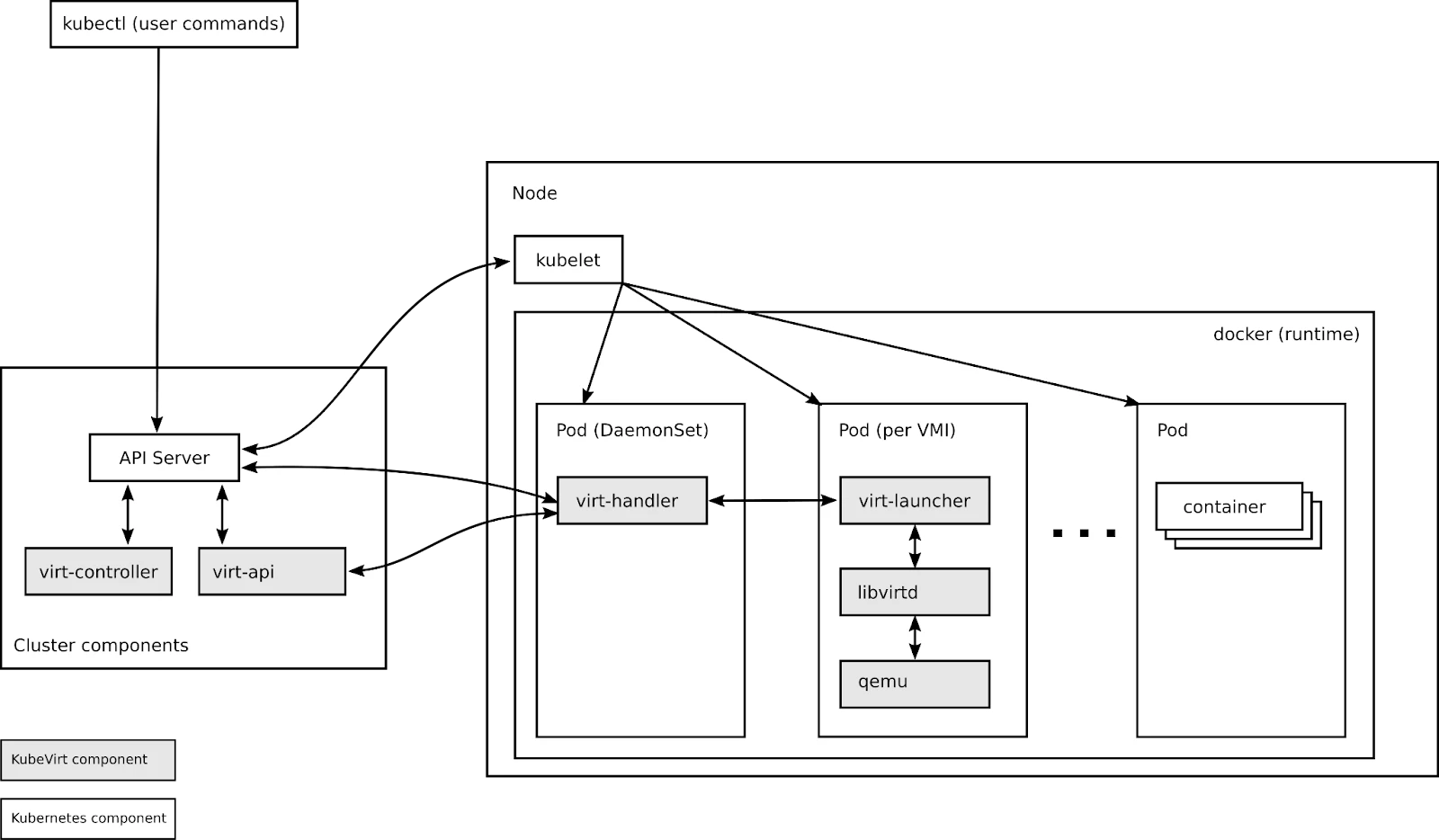

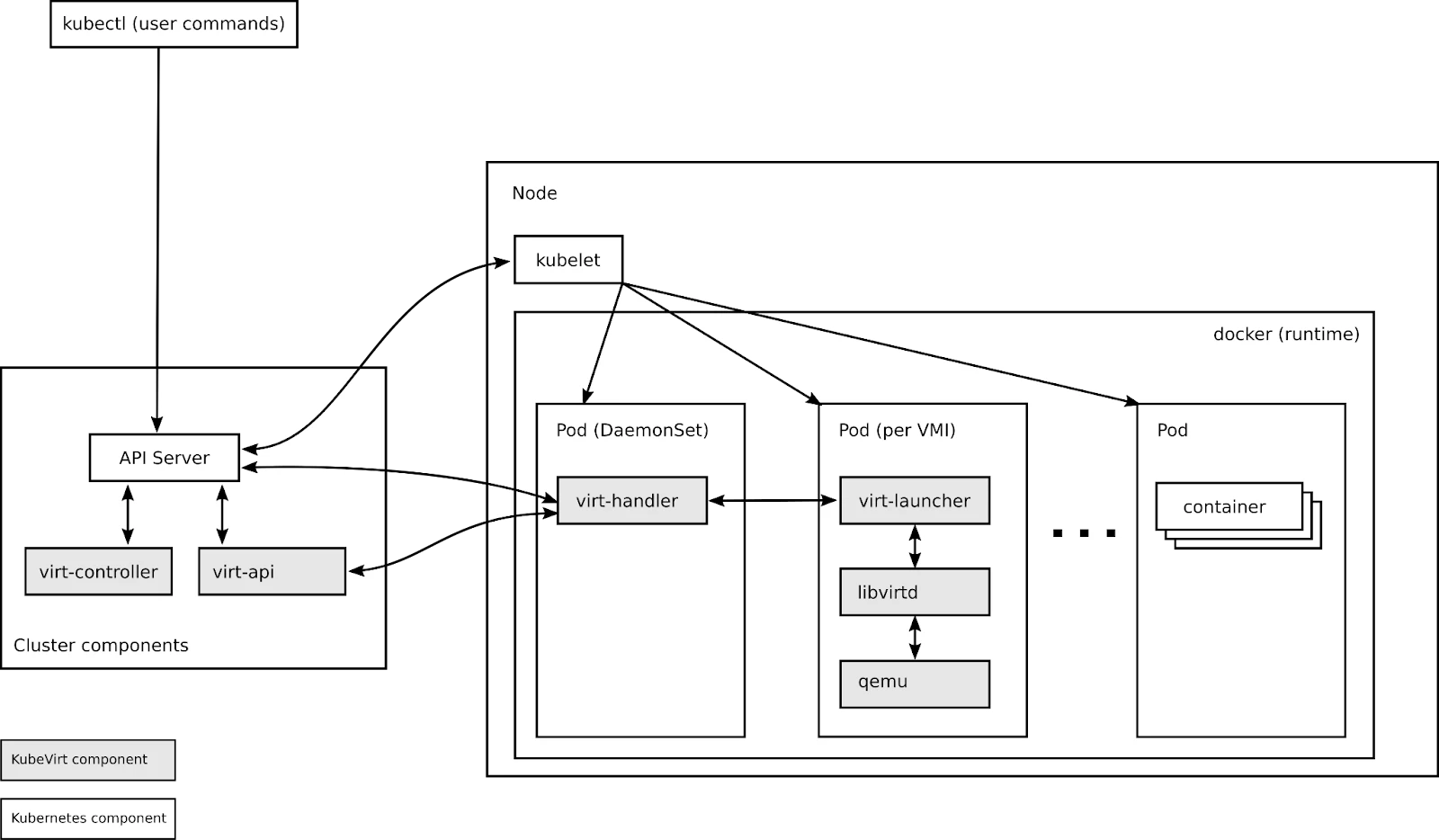

KubeVirt installs as an add-on to any standard Kubernetes cluster. It introduces new Custom Resource Definitions (CRD) that teach Kubernetes how to understand and manage virtual machines. The VirtualMachine resource in KubeVirt defines a VM specification. The VirtualMachineInstance represents a running VM.

Under the hood, KubeVirt uses the same virtualization technology you trust. QEMU provides the emulation layer. KVM delivers hardware-accelerated virtualization on Linux hosts. These technologies power OpenStack, Proxmox, and countless enterprise virtualization platforms. The underlying hypervisor is mature and production-proven.

Each VM runs inside a Kubernetes pod. The pod hosts a container that runs the VM process. From the Kubernetes scheduler’s perspective, this pod consumes CPU, memory, and storage like any other workload. The scheduler places VMs on nodes using the same logic it uses for containers. Resource requests, node affinity, and anti-affinity rules all apply.

This architecture delivers a critical benefit. Your VMs become Kubernetes-native resources. You manage them with kubectl or through the available dashboard UI in commercial platforms such as Red Hat OpenShift Virtualization. You define them in YAML manifests. You store those manifests in Git. The declarative model from Part 1 applies directly to your virtual machines.

Consider a simple VM definition:

apiVersion: kubevirt.io/v1

kind: VirtualMachine

metadata:

name: legacy-app-server

spec:

running: true

template:

spec:

domain:

resources:

requests:

memory: 4Gi

cpu: 2

devices:

disks:

- name: root-disk

disk:

bus: virtio

volumes:

- name: root-disk

persistentVolumeClaim:

claimName: legacy-app-disk

The above manifest declares a VM with 4GB of memory and 2 CPU cores. It references a persistent volume claim for storage. Apply this manifest with kubectl and Kubernetes to create your VM. Delete the manifest, and Kubernetes removes the VM. The lifecycle seamlessly integrates with GitOps workflows we discussed in Part 1.

Running VMs and Containers Together

The unified control plane changes how you think about workload placement. VMs and containers share the same cluster. They share the same network. They share the same storage infrastructure. They even share the same nodes if you configure them that way.

Network communication happens naturally. A containerized frontend can connect to a VM-based database using standard Kubernetes Service resources. The VM gets an IP address from the pod network. Service discovery works identically. A container calls the database service name, and Kubernetes routes traffic to the VM.

Storage works through the same PersistentVolume system. Your VM disks live on persistent volumes backed by your storage infrastructure. Portworx, Ceph, NetApp, and other storage providers work through CSI drivers. The VM sees a block device. Kubernetes handles the provisioning, attachment, and replication. Storage policies apply to VM workloads exactly as they apply to container workloads.

This convergence eliminates infrastructure silos. You no longer need separate VMware clusters and Kubernetes clusters. You no longer need separate storage pools for VMs and containers. You no longer need separate network configurations. One infrastructure serves all workloads.

The operational benefits compound over time. Your monitoring tools integrate with a single platform rather than two. Your backup strategy covers one environment instead of two. Your team learns one set of tools instead of two. Operational complexity decreases as workloads consolidate.

When to Use VMs vs Containers

KubeVirt gives you a choice. That choice requires a framework for deciding which workload type fits each application.

Use containers when the application is designed for them. Microservices, stateless web applications, and modern 12-factor apps belong in containers. Applications that start fast, scale horizontally, and tolerate instance replacement thrive in container environments. If your development team builds and tests in containers, deploy to containers as well.

Use VMs when the workload requires them. Windows Server applications often need VM environments. Commercial software that ships as VM images or ISO files needs VMs. Legacy applications with specific kernel requirements or driver dependencies need VMs. Applications that assume long-running processes and persistent local state often fit better in VMs.

Use VMs for lift-and-shift migrations. When you move workloads from VMware to Kubernetes, starting with VMs minimizes risk. The application runs in a familiar environment. The migration validates your Kubernetes infrastructure. The VM proves that storage, networking, and compute work correctly. Containerization becomes a later optimization rather than an upfront requirement.

Use containers for new development. When teams build new applications, guide them toward containers. The container ecosystem offers better tooling for modern development workflows. Container images are smaller and start faster. CI/CD pipelines integrate more naturally. New applications should adopt new patterns.

The decision often comes down to the effort required for migration versus the operational benefit. Containerizing a legacy application requires development work. Running that application as a VM on KubeVirt requires minimal changes. If the application works and nobody plans to modify it, the VM approach makes sense. If the application needs active development, investing in containerization pays dividends over time.

Managing Both Workload Types

Your existing Kubernetes skills apply directly to KubeVirt VMs. The kubectl commands you learn for containers work for virtual machines with minor variations.

kubectl get virtualmachines lists your VMs. kubectl describe virtualmachine shows configuration details. kubectl delete virtualmachine removes a VM. kubectl logs retrieves console output. The CLI experience remains consistent.

Helm charts can deploy VMs alongside containers. A single chart defines your application with its containerized components and VM dependencies. One deployment command provisions everything. One upgrade command updates everything. The application becomes a cohesive unit regardless of underlying workload types.

RBAC policies control access uniformly. You define roles that grant permissions to create, modify, or delete VMs. You bind those roles to users or service accounts. The authorization model matches what you use for container workloads.

Monitoring integrates through standard Kubernetes mechanisms. KubeVirt exports metrics in Prometheus format. CPU utilization, memory consumption, disk I/O, and network traffic all appear in your existing dashboards. Alerts fire based on the same rules you define for containers.

For VMware professionals, this offers a major simplification. You only need to manage one platform instead of two. Your skills transfer directly, and your tools integrate seamlessly. The operational approach stays consistent across all workloads.

The Path Forward

KubeVirt provides your transition path. It removes the requirement to containerize everything before adopting Kubernetes. It lets you migrate workloads incrementally. It preserves your VM investments while enabling container adoption.

Start by identifying candidates for early migration. Look for VMs that are relatively standalone. Development and test environments make good first targets. Non-critical internal applications reduce risk while you learn. Success with simple workloads builds confidence for complex ones.

Plan for eventual containerization where it makes sense. KubeVirt buys you time, but should not become a permanent destination for every workload. Applications under active development should move toward containers over time. Lift-and-shift gets workloads onto Kubernetes quickly. Refactoring to containers in the long term delivers the full benefits of cloud native architecture.

Some workloads will remain VMs indefinitely. Commercial software that ships only as VM images will remain on VMs. Legacy applications that nobody will ever modify will stay on VMs. This is acceptable. KubeVirt makes those VMs first-class citizens in your Kubernetes environment.

The series continues with Part 3, where we map the entire VMware SDDC stack to its Kubernetes equivalents. You will see how vSphere, vSAN, and NSX concepts translate to the cloud native world. The mental model you build will anchor every subsequent discussion of compute, storage, networking, and security.

KubeVirt bridges your present to your future. Use that bridge to move forward at a pace your organization can sustain. The destination is cloud native infrastructure. The journey accommodates your existing reality.

Demystifying Kubernetes – Blog series