This blog is part of Demystifying Kubernetes for the VMware Admin, a 10-part blog series that gives VMware admins a clear roadmap into Kubernetes. The series connects familiar VMware concepts to Kubernetes—covering compute, storage, networking, security, operations, and more—so teams can modernize with confidence and plan for what comes next.

You understand compute virtualization. ESXi hosts run your VMs. Clusters pool those hosts together. DRS balances workloads automatically. vCenter provides centralized management. These concepts translate directly to Kubernetes.

The terminology changes. The operational model shifts. The underlying principles remain exactly the same: abstract physical resources, schedule workloads intelligently, and provide high availability when things fail.

This chapter maps your ESXi and vSphere knowledge to Kubernetes compute concepts. By the end, you will understand how nodes, pods, and containers relate to the infrastructure you already manage. You will see where DRS and the Kubernetes scheduler align and where they differ.

The Foundation: ESXi Hosts vs Kubernetes Nodes

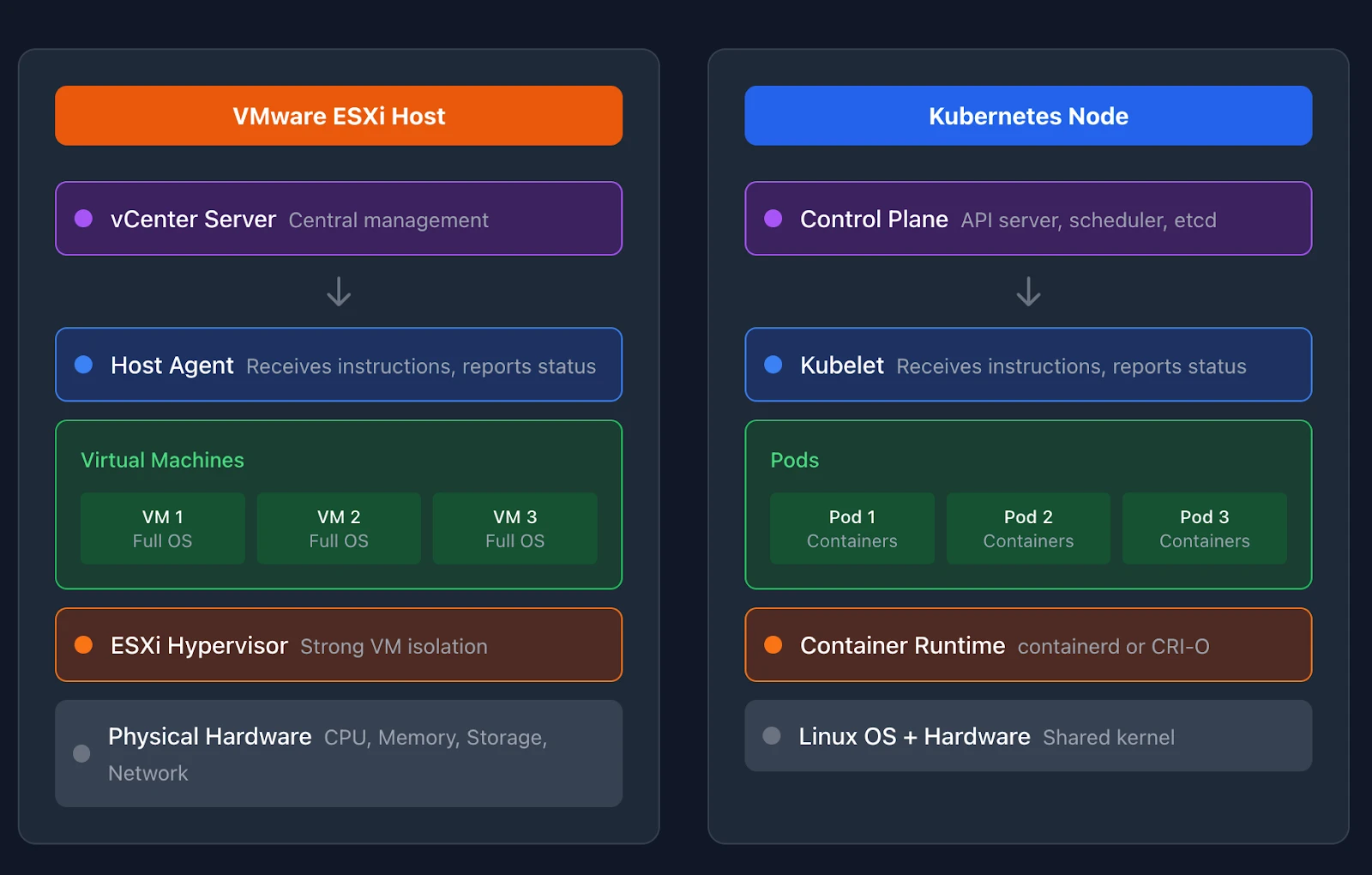

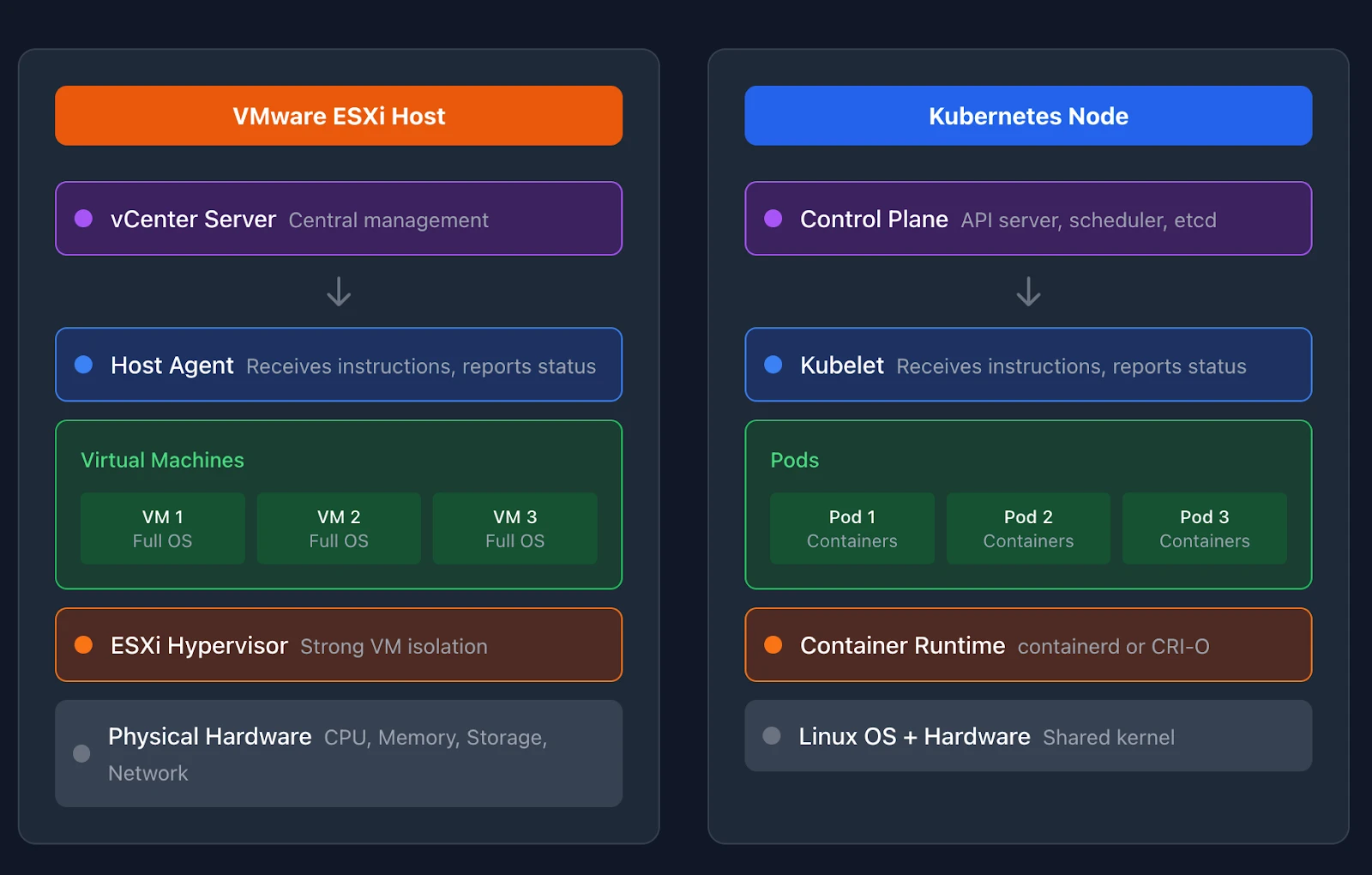

An ESXi host runs the hypervisor that enables virtualization. Physical CPU, memory, network, and storage become pooled resources available to virtual machines. You manage ESXi hosts through vCenter.

A Kubernetes node serves the same foundational role. Nodes are machines that run containerized workloads. They provide CPU, memory, and storage to pods. Each node runs a few key components that make this possible.

The kubelet runs on every node. This agent communicates with the Kubernetes control plane, receives instructions about which pods to run, and reports node status back to the cluster. The kubelet is to a node what the ESXi host agent is to vSphere. It makes the node manageable.

Every node also runs a container runtime. These runtimes pull container images and start the actual containers that run your applications. The container runtime sits below Kubernetes in the stack, similar to how the hypervisor sits below vCenter.

A third component, kube-proxy, handles Service routing on each node. It maintains network rules that direct traffic to the correct pods when you access a Service’s virtual IP. Think of it as the Service proxy that makes Service VIPs and load balancing work. Some CNI plugins like Cilium replace kube-proxy entirely with their own implementation. We will cover networking in depth in Part 6.

When you add an ESXi host to a vSphere cluster, vCenter discovers its resources and makes them available for VM placement. Kubernetes works similarly. When a node joins a cluster, the kubelet registers with the control plane. The scheduler then considers that node when placing new workloads.

The Workload: VMs vs Pods vs Containers

Understanding the relationship between VMs, pods, and containers requires careful attention. These are different levels of abstraction with different isolation characteristics.

A virtual machine on ESXi has its own operating system. The hypervisor provides strong isolation between VMs. Each VM boots its own kernel, runs its own init system, and manages its own processes. You can run Windows and Linux VMs side by side on the same ESXi host because each VM is fully isolated.

Containers share the host operating system kernel. A container includes your application and its dependencies, but not a full operating system. Multiple containers on the same node all use that node’s Linux kernel. This makes containers lighter than VMs but provides weaker isolation.

A pod is a Kubernetes abstraction that groups one or more containers. Containers within a pod share the same network namespace and can communicate over localhost using IPC and ITS protocols. They also share storage volumes. Pods are the smallest deployable unit in Kubernetes.

For VMware administrators, the most useful mental model is this: think of a pod as the Kubernetes equivalent of “the thing you deploy and scale.” You deploy VMs in vSphere. You deploy pods in Kubernetes.

The abstraction levels differ in practice. A single pod might run one container for your main application and another for logging. These containers start and stop together. They share an IP address. This sidecar pattern has no direct equivalent in the VM world.

Most production workloads run pods through higher-level controllers. Deployments manage stateless applications and ensure your desired number of replicas run at all times. StatefulSets manage stateful applications with stable network identities and persistent storage. These controllers are closer to how you think about deploying and scaling workloads than raw pods.

Resource Scheduling: DRS vs the Kubernetes Scheduler

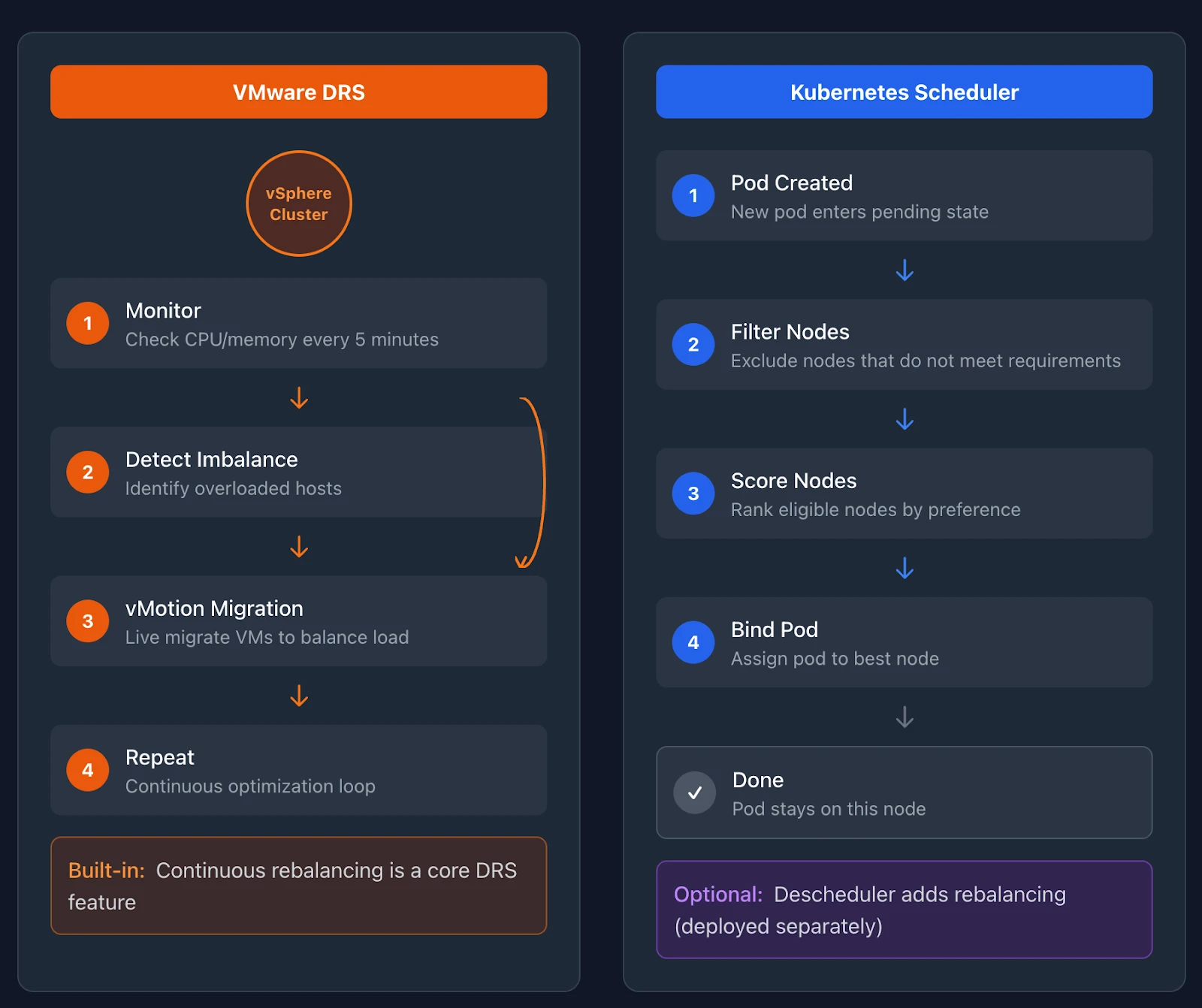

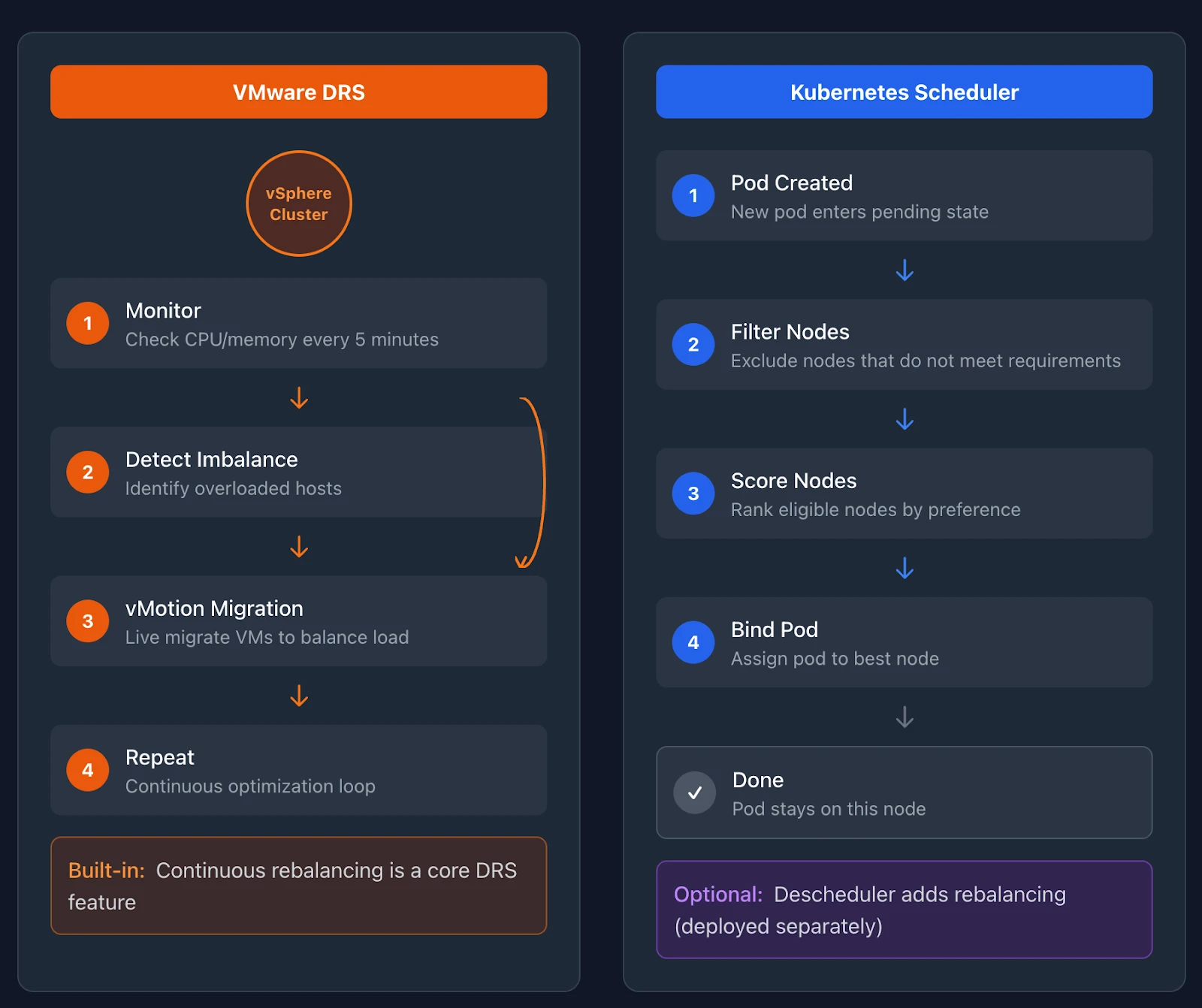

DRS monitors CPU and memory utilization across your vSphere cluster. When it detects an imbalance, it migrates VMs between hosts using vMotion. The goal is to balance resource distribution and prevent hotspots.

The Kubernetes scheduler handles initial pod placement. When you create a pod, the scheduler evaluates all available nodes and selects the best one based on resource requests, constraints, and scoring rules.

A critical difference exists here. DRS provides ongoing workload balancing through live migration. The Kubernetes scheduler only places pods at creation time. Once a pod runs on a node, the default scheduler does not move it.

This distinction surprises many VMware administrators. DRS continuously optimizes your cluster. The Kubernetes scheduler makes a decision once and leaves pods in place.

Kubernetes addresses ongoing optimization differently. The Descheduler project provides cluster rebalancing capabilities. It runs as an optional component, evaluates pod placement against policies, and evicts pods that should move. When the Descheduler evicts a pod, the controller creates a replacement, and the scheduler places it on a better node.

The Descheduler is not a standard Kubernetes component. You deploy it separately if you need rebalancing. Many managed Kubernetes services provide built-in alternatives. The important point is that Kubernetes separates initial placement from ongoing optimization.

Both systems consider resource requests when scheduling. In vSphere, you configure VM reservations and limits for CPU and memory. In Kubernetes, you specify resource requests and limits in pod specifications.

Requests tell the scheduler how much CPU and memory your pod needs. The scheduler will not place a pod on a node unless that node has enough unrequested capacity. This prevents overcommitment at the scheduling layer. Limits define the maximum resources a container can consume. If a container exceeds its memory limit, Kubernetes terminates it.

Requests impact placement and quality of service. Kubernetes scheduler honors the requests so that the requested CPU and memory fit, and the runtime enforces isolation with cgroups. But this is not the same as vSphere reservations that carve out untouchable capacity. CPU is compressible and managed through the Completely Fair Scheduler (CFS) shares and throttling. Memory requests affect scheduling and eviction priority but do not create dedicated physical partitions. Under pressure, Kubernetes evicts lower-priority pods rather than guaranteeing reserved capacity the way vSphere does.

Affinity and anti-affinity rules exist in both systems. DRS supports VM-VM and VM-Host rules that keep certain workloads together or apart. Kubernetes provides pod affinity, pod anti-affinity, and node affinity. You can require that two pods run on the same node, require they run on different nodes, or prefer certain node characteristics without mandating them.

Topology spread constraints in Kubernetes distribute pods across failure domains. You can ensure pods spread evenly across availability zones or nodes. This capability closely resembles VM-Host anti-affinity rules, which distribute VMs across hosts to improve availability.

The Control Plane: vCenter vs Kubernetes API Server

vCenter Server is your central management point for vSphere. It maintains the inventory of hosts, clusters, VMs, and networks. It provides the interface for configuration and operations. vCenter runs DRS, manages vMotion, and stores configuration in its database.

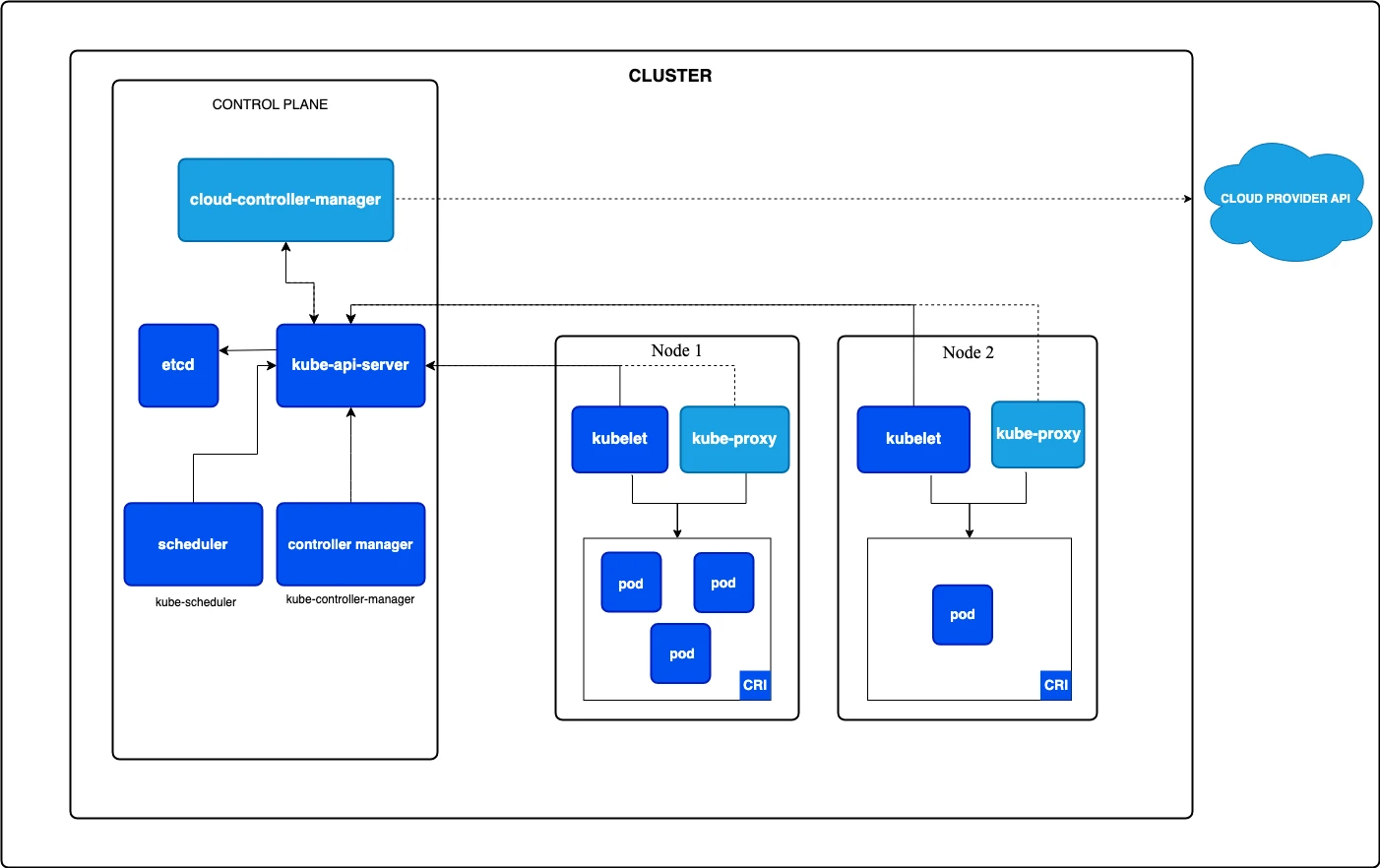

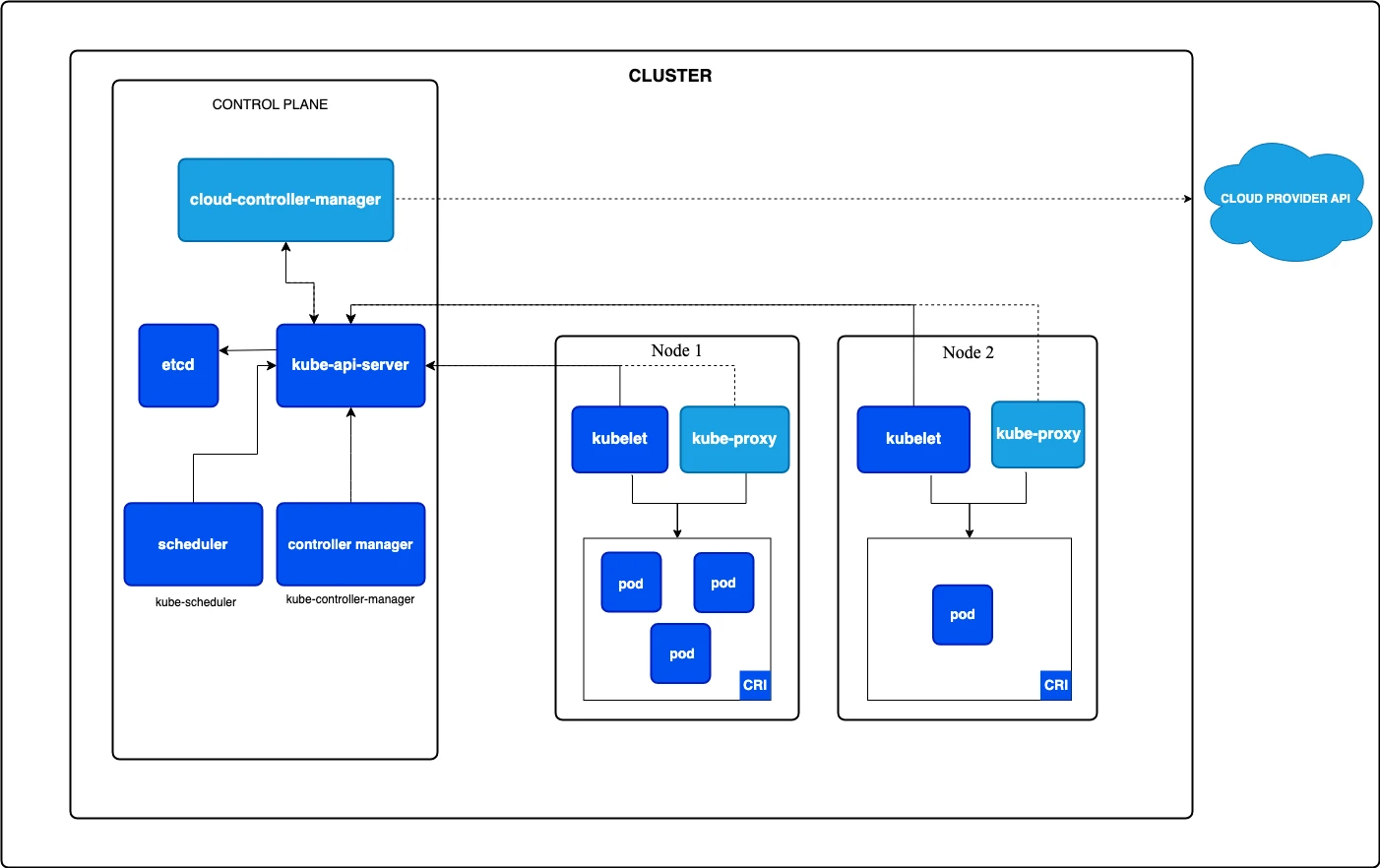

Kubernetes distributes these responsibilities across multiple control plane components.

The API server is the frontend for all cluster operations. Every kubectl command, every controller action, and every kubelet status update flows through the API server. It validates requests, notifies interested components of changes, and serves as the gateway to cluster state.

etcd stores all cluster state. This distributed key-value store holds the definitions of every pod, service, deployment, and configuration in your cluster. The API server reads from and writes to etcd. Without etcd, the cluster loses its memory.

The scheduler watches for unscheduled pods and assigns them to nodes. It functions as a single-purpose component focused on placement decisions.

Controller managers run control loops that reconcile the desired state with the actual state. When you create a Deployment requesting three pod replicas, the Deployment controller creates three pods. When a node fails, the node controller marks it as unavailable, and other controllers create replacement pods elsewhere.

This architecture differs from vCenter’s monolithic approach. vCenter combines inventory management, scheduling, migration, and operations into a single server. Kubernetes separates these concerns into components that communicate through the API server.

High availability patterns also differ. vCenter HA requires vCenter High Availability configuration with witness nodes. Kubernetes control planes achieve HA by running multiple replicas of each component behind a load balancer, with etcd running as a clustered store.

In managed Kubernetes services like EKS, AKS, and GKE, the cloud provider operates the control plane. You interact with the API server without managing etcd or the scheduler directly. This resembles how VMware Cloud on AWS abstracts vCenter management from customers. Note that VMware Cloud on AWS is now available directly from Broadcom rather than through AWS reselling.

Putting the Pieces Together

Your ESXi cluster has hosts managed by vCenter. DRS schedules VMs onto hosts and rebalances them over time. Each VM runs a full operating system isolated by the hypervisor.

Your Kubernetes cluster has nodes that register with the control plane. The scheduler places pods onto nodes at creation time. Each pod runs one or more containers that share the host kernel.

The kubelet on each node acts as the local agent, similar to the ESXi host agent. The container runtime runs below the kubelet, providing the actual container execution.

Resource management uses requests and limits rather than reservations and limits. Requests drive scheduling and QoS classification, with cgroups enforcing isolation at runtime. Scheduling rules use affinity, anti-affinity, and topology spread constraints instead of DRS rules.

The control plane distributes responsibilities across components rather than centralizing them in vCenter. etcd stores state. The API server serves as the frontend for all communication. The scheduler handles placement. Controllers handle reconciliation.

These differences matter for operations. Kubernetes expects workloads to fail and restart. Pods are ephemeral by default. The system constantly reconciles the actual state with the desired state. Your VM mindset treats workloads as long-lived and stable. Kubernetes assumes they will move, restart, and scale.

Part 5 examines storage. You will learn how vSAN concepts translate to persistent volumes, how storage policies become storage classes, and how the Container Storage Interface standardizes storage integration across providers.

Demystifying Kubernetes – Blog series