This blog is part of Demystifying Kubernetes for the VMware Admin, a 10-part blog series that gives VMware admins a clear roadmap into Kubernetes. The series connects familiar VMware concepts to Kubernetes—covering compute, storage, networking, security, operations, and more—so teams can modernize with confidence and plan for what comes next.

You built your career on VMware’s Software Defined Data Center. You know how vSphere, vSAN, and NSX work together. You understand the management layer. The components make sense because you have deployed, configured, and troubleshot them for years.

Kubernetes has equivalent components for almost every layer of your VMware stack. The names change. The interfaces change. The underlying concepts and the core building blocks remain remarkably familiar.

This part provides the mental map you need. We will walk through VMware Cloud Foundation layer by layer and identify what each component is replaced by in the cloud native world. Once you see the parallels, everything else in this series will click into place.

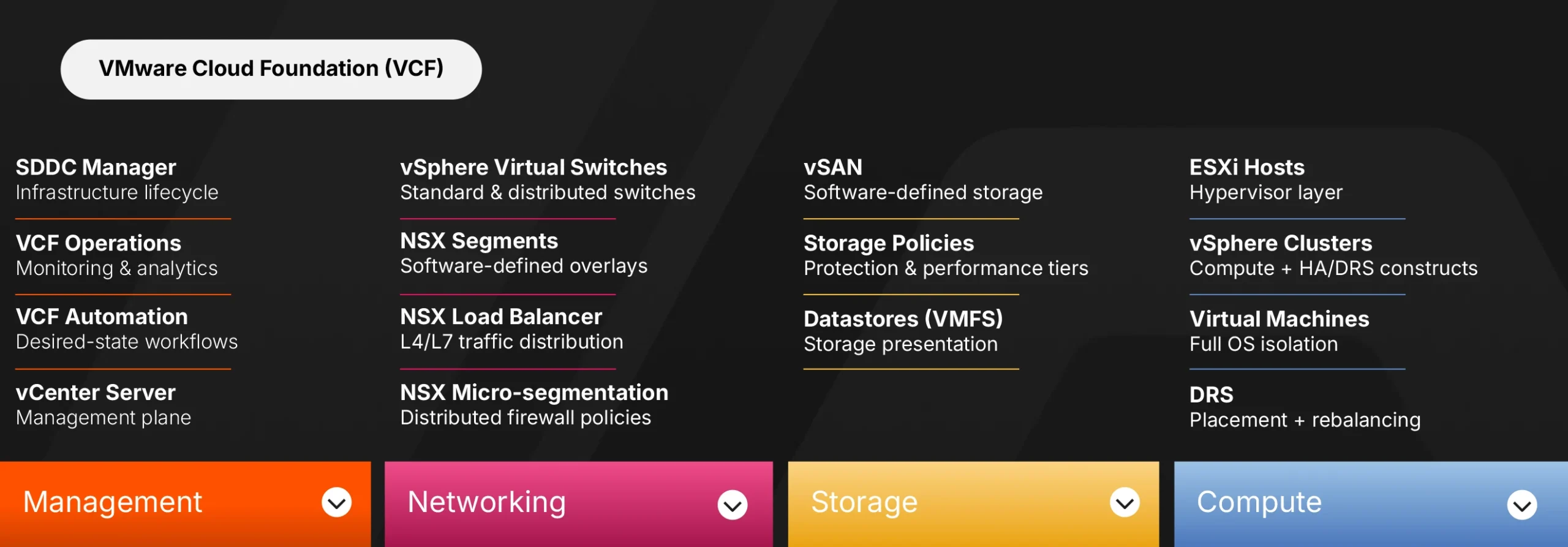

The VMware Cloud Foundation Stack

VMware Cloud Foundation represents the complete Software Defined Data Center (SDDC). VCF 9.0 bundles compute, storage, networking, and management into a unified platform. You deploy VCF as an integrated stack rather than assembling individual products.

The stack has four primary layers.

Compute sits at the foundation. ESXi hosts form clusters managed by vCenter Server. VMs run on these hosts. vCenter handles provisioning, resource management, and lifecycle operations. DRS automatically balances workloads across hosts, including moving running VMs to fix hotspots. vSphere HA restarts VMs when hosts fail.

Storage builds on top of compute. vSAN aggregates local storage from ESXi hosts into a shared datastore. Storage policies define protection levels, performance tiers, and capacity allocation. VMs consume storage through VMFS or vSAN datastores without knowing which physical disks hold their data.

Networking connects everything. vSphere virtual switches provide Layer 2 connectivity: standard switches per host, distributed switches across hosts. NSX adds software-defined networking and security on top, including segmentation, routing, microsegmentation, and integrated network services. This layered approach separates basic connectivity from advanced network virtualization.

Management ties the layers together. SDDC Manager orchestrates bring-up and upgrades, but in VCF 9, its UI is deprecated, and many workflows surface in VCF Operations and the vSphere Client. VCF Operations provides monitoring and operational analytics with integrated log analysis. VCF Operations for Logs provides centralized log management. VCF Automation provides self-service and workflow automation. vCenter serves as the primary interface for day-to-day administration.

This architecture works. Enterprises run production workloads on VCF because the integration is proven and the operational model is well understood.

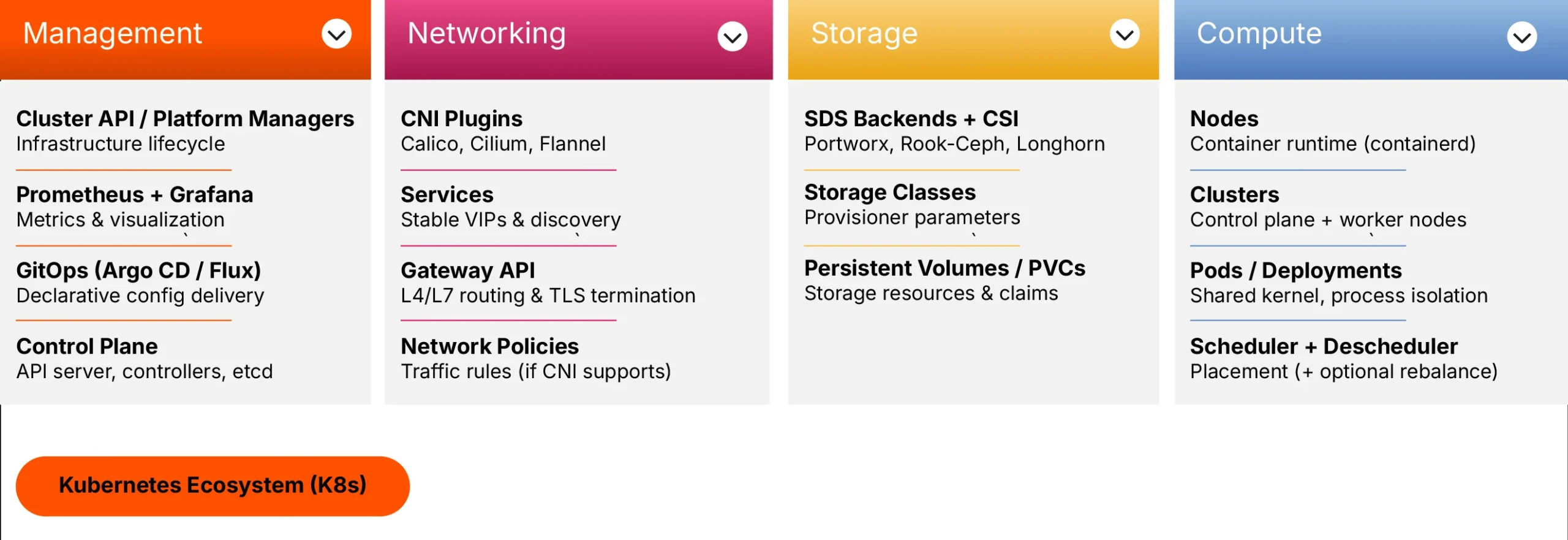

The Kubernetes Cloud Native Stack

Kubernetes organizes infrastructure differently. Instead of having a single vendor provide all components, the cloud native ecosystem relies on interchangeable parts that follow open standards.

The stack has the same four layers. The components change.

Compute in Kubernetes means nodes and pods. Nodes are servers running the kubelet agent and a container runtime. Pods are groups of containers that share a network and storage. The Kubernetes scheduler places pods on nodes based on resource requirements and constraints. When nodes fail, controllers like Deployments or StatefulSets create replacement pods. The scheduler then places those new pods on healthy nodes.

Storage uses the Container Storage Interface (CSI) standard. CSI is an interface specification that connects Kubernetes to storage backends. Persistent Volumes represent storage resources. Persistent Volume Claims let applications request storage without knowing the underlying implementation. Storage Classes define tiers with different characteristics, passed as parameters to the storage provisioner.

Networking follows the Container Network Interface (CNI) specification. CNI plugins like Calico, Cilium, or Flannel provide pod networking. Services expose applications internally and provide stable virtual IPs. The recently added Gateway API handles external HTTP/HTTPS traffic, including routing and SSL termination. Network Policies control traffic flow between pods, though enforcement depends on your CNI plugin supporting them.

Management spans multiple tools. The Kubernetes control plane includes the API server as the front door, controllers for reconciliation, the scheduler for placement, and etcd as the backing state store. Prometheus collects metrics. Grafana visualizes data. GitOps tools like Argo CD or Flux manage application and configuration deployments declaratively. Platform engineering teams often build internal developer platforms on top of these components.

No single vendor owns this stack. You choose components based on your requirements. The interfaces between components follow open specifications, so you can swap implementations without rebuilding your entire platform.

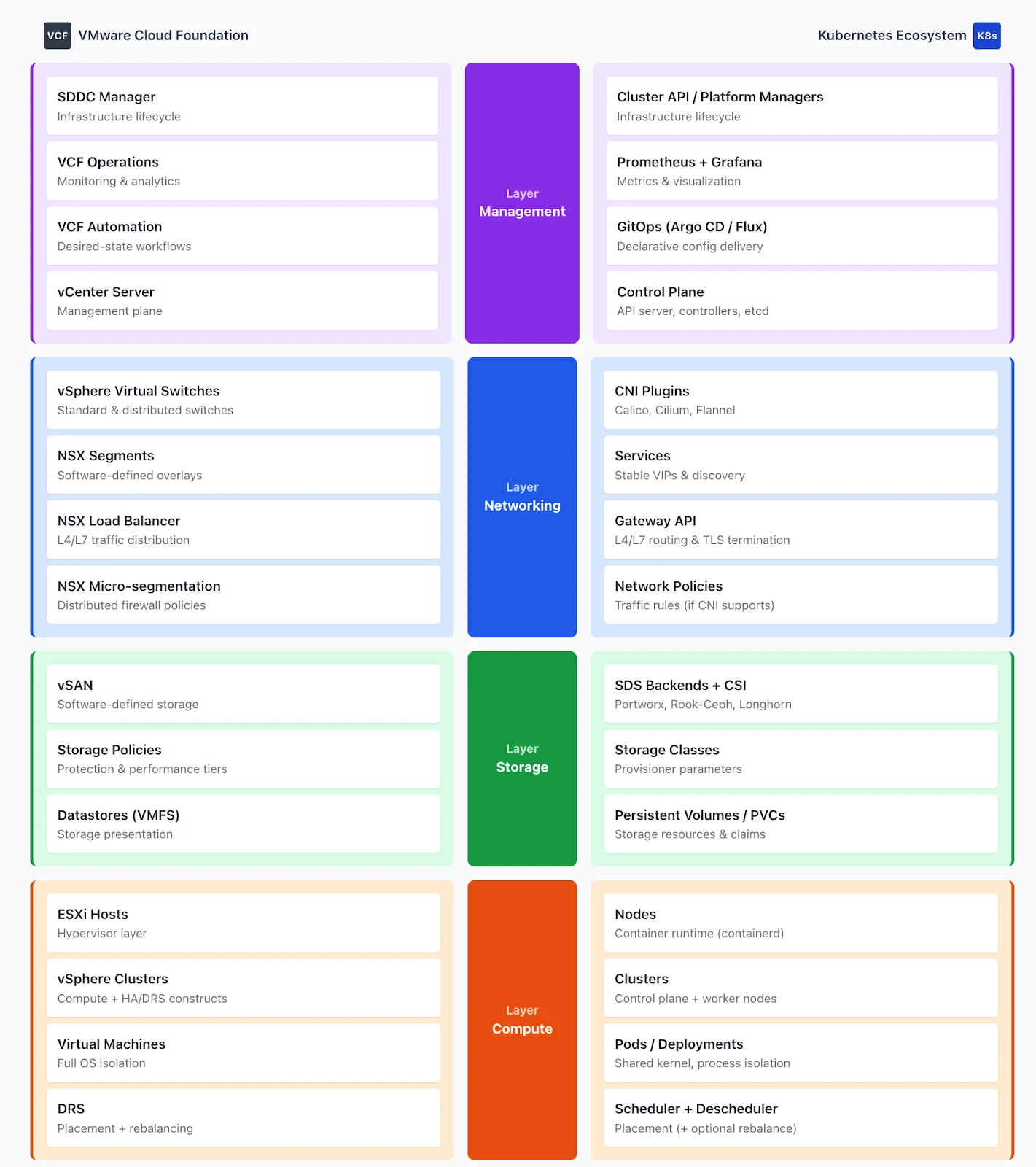

The Conceptual Mapping

Here is how VMware components map to their Kubernetes equivalents. These mappings provide mental anchors, not exact equivalences. Each platform has distinct design philosophies, making perfect one-to-one comparisons impossible.

vSphere Clusters map to Kubernetes Clusters. Both groups compute resources into manageable units. Both support workload isolation and resource pooling. The difference: Kubernetes clusters include control plane services and an API contract. vSphere clusters are primarily compute constructs with HA and DRS behavior.

ESXi Hosts map to Kubernetes Nodes. Both provide the compute substrate. ESXi runs a hypervisor that creates hardware abstraction. Kubernetes nodes run a container runtime, such as containerd. The kubelet agent on each node reports status and accepts work from the control plane. The kubelet is an agent, not a virtualization layer.

Virtual Machines map loosely to Pods, but the analogy has limits. VMs provide full operating system isolation with separate kernels. Pods share the host kernel and isolate processes through namespaces and cgroups. The isolation model differs significantly. If you want a closer match for “the thing I deploy and scale,” think of Deployments or StatefulSets as the VM equivalent. These controllers own pods and manage their lifecycle.

vCenter maps to the Kubernetes Control Plane. vCenter provides the management plane for vSphere. The Kubernetes equivalent includes multiple components working together: the API server as the entry point, controllers that reconcile desired state with actual state, the scheduler that places workloads, and etcd that stores cluster state. Comparing vCenter to the API server alone oversimplifies the architecture, but it does help with the mental model.

DRS maps to Scheduling plus Rebalancing. DRS handles initial VM placement and ongoing balancing. It moves running VMs to fix resource hotspots. Kubernetes scheduling works differently. The scheduler selects nodes for new or unscheduled pods. Kubernetes does not continuously rebalance running pods by default. If you want DRS-like rebalance behavior, you add a Descheduler. The Descheduler evicts pods based on policies, and the scheduler then places them on better-suited nodes.

vSAN maps to Kubernetes-native software-defined storage backends exposed via CSI. CSI itself is an interface standard, not a storage system. The actual storage comes from backends such as Portworx, Rook Ceph, or Longhorn. These solutions aggregate and manage storage. CSI provides the integration layer that exposes storage capabilities to pods.

Storage Policies map to Storage Classes. Both define storage tiers with specific characteristics. A VMware storage policy might specify RAID level, encryption, and performance tier. A Kubernetes Storage Class specifies a provisioner and parameters. Features like replication and encryption depend on the underlying storage backend. The Storage Class passes parameters to the provisioner, which translates them into backend-specific configurations. Portworx, for example, uses a repl parameter to set the replication factor (up to three copies across nodes), similar to vSAN’s Failures to Tolerate setting. For encryption, Portworx accepts a secure: “true” parameter that enables AES-256 volume encryption, with key management through Kubernetes Secrets or external providers like Vault, AWS KMS, or Google KMS.

vSphere Virtual Switches map to CNI Plugins for basic connectivity. Both provide the foundational network layer. Standard switches and distributed switches in vSphere give VMs Layer 2 connectivity. CNI plugins give pods network connectivity within and across nodes.

NSX maps to Network Policies plus advanced networking features. NSX adds segments, routing, micro-segmentation, and load balancing on top of vSphere networking. In Kubernetes, Network Policies define traffic rules between pods. Service meshes like Istio or Linkerd add advanced traffic management, observability, and security. One caveat: Network Policy enforcement requires a CNI plugin that supports it. Not all do, but if you choose a plugin like Cilium or Calico, you can implement fine-grained network policies.

NSX Load Balancer maps to Services plus Gateway API. Both distribute traffic to backend workloads. Kubernetes Services provide stable virtual IPs and internal discovery. Service type LoadBalancer integrates with external load balancers. Gateway API is for Layer 4 and Layer 7 HTTP/HTTPS routing. The separation of concerns differs from NSX’s integrated approach.

VCF Operations maps to Prometheus and Grafana. VCF Operations provides monitoring, operational analytics, and integrated log analysis. Prometheus and Grafana fill that role in Kubernetes. VCF Operations for Logs has an equivalent in centralized logging solutions such as Loki, Elasticsearch, or Fluentd.

VCF Automation maps to GitOps tools. VCF Automation handles desired-state delivery and self-service workflows. GitOps tools like Argo CD provide similar declarative configuration management for applications and cluster add-ons.

SDDC Manager maps to Infrastructure Lifecycle Management tools. SDDC Manager handles bring-up, upgrades, and lifecycle of VCF stack components. The Kubernetes equivalent is cluster lifecycle management via tools such as Cluster API (CAPI) or vendor-specific platform managers. GitOps handles application and configuration delivery, a different layer of the problem.

The Simplified Stack Comparison

Think of the stacks as parallel structures with equivalent layers, while respecting their architectural differences.

At the compute layer, ESXi hosts running VMs map to Kubernetes nodes running pods. The isolation boundary moves from a hypervisor to the host OS kernel (namespaces and cgroups), with the container runtime managing packaging and execution.

At the storage layer, vSAN with storage policies maps to software-defined storage backends exposed through CSI with Storage Classes. Data services such as snapshots, replication, and encryption are available in both worlds, but their implementation depends on your chosen storage backend.

At the networking layer, vSphere switches plus NSX map to CNI plugins combined with the Gateway API and Network Policies. Kubernetes separates what VMware layers (basic connectivity in vSphere, advanced services in NSX). Network segmentation moves from distributed port groups and NSX segments to namespaces and Network Policies.

At the management layer, vCenter maps to the Kubernetes control plane. SDDC Manager maps to cluster lifecycle tools. VCF Operations and Automation map to observability and GitOps tooling. The operational model shifts from GUI-driven configuration to declarative manifests stored in Git.

Seven or eight component areas in VMware have counterparts in Kubernetes. The abstraction levels align at a conceptual level. The implementations and design philosophies differ in important ways that this series will explore.

Why This Mapping Matters

Understanding these parallels accelerates your learning. You already know what DRS does. Learning that Kubernetes scheduling handles initial placement while the Descheduler handles rebalancing takes less effort than learning scheduling concepts from scratch.

The mapping also helps you evaluate solutions. When a vendor pitches a Kubernetes storage product, you can assess it against your vSAN experience. Does it support snapshots? What about replication? How does it handle node failures? Your VMware knowledge frames the right questions. Just remember that features depend on the storage backend, not the CSI interface.

Most importantly, this mapping provides context for everything that follows in this series. Part 4 will explore compute in depth. Part 5 covers storage. Part 6 addresses networking. Each part builds on this foundation, showing you how familiar concepts translate to cloud native implementations while highlighting where the platforms diverge.

Your SDDC expertise transfers. The nuances matter. The next step is learning both the new approach and the new mental models.

Demystifying Kubernetes – Blog series

- Chapter 1: From ClickOps to GitOps: Why the Paradigm Is Shifting

Economic pressure, operational philosophy changes, and what this means for VMware professionals. - Chapter 2: KubeVirt: Running Virtual Machines in a Kubernetes World

How VMs and containers coexist—and why KubeVirt is the practical bridge forward. - Chapter 3: Mapping the Stack: From VMware SDDC to Cloud-Native Architecture

A mental model that translates vSphere, vSAN, and NSX into Kubernetes equivalents. - Chapter 4: Compute Reimagined: ESXi Hosts vs Kubernetes Nodes

How scheduling, abstraction, and control planes differ between hypervisors and Kubernetes. - Chapter 5: Storage Evolution: From Datastores to Persistent Volumes

Translating vSAN concepts into container-native storage and CSI-driven architectures. - Chapter 6: Networking Translated: NSX and the Kubernetes Networking Model

CNI plugins, services, ingress, and service meshes explained for VMware practitioners. - Chapter 7: Security Models Compared: vSphere Security vs Kubernetes Security

RBAC, isolation, policy enforcement, and shared responsibility in a cloud-native world. - Chapter 8: Day 2 Operations: Monitoring, Lifecycle, and Reliability

How observability, upgrades, backup, and DR work once Kubernetes is in charge. - Chapter 9: Planning the Migration: From VMware Estate to Kubernetes Platform

Assessment frameworks, migration strategies, team structure, and common pitfalls. - Chapter 10: Beyond Migration: Building a Cloud-Native Operating Model

Platform engineering, GitOps, extensibility, and preparing for what comes next.

Share

Subscribe for Updates

About Us

Portworx is the leader in cloud native storage for containers.

Thanks for subscribing!

Janakiram MSV

Industry AnalystJanakiram MSV (Jani) is a practicing architect, research analyst, and advisor to Silicon Valley startups. He focuses on the convergence of modern infrastructure powered by cloud-native technology and machine intelligence driven by generative AI. Before becoming an entrepreneur, he spent over a decade as a product manager and technology evangelist at Microsoft Corporation and Amazon Web Services. Janakiram regularly writes for Forbes, InfoWorld, and The New Stack, covering the latest from the technology industry. He is an international keynote speaker for internal sales conferences, product launches, and user conferences hosted by technology companies of all sizes.

Related posts

Chapter 2: KubeVirt: The Bridge Between Worlds

Chapter 1: The Paradigm Shift: From ClickOps to GitOps

Revolutionizing Edge Deployments: Portworx and Red Hat